As extreme climate events become more frequent, it’s hard to ignore the impact that shifting weather patterns, droughts, floods, and storms have on disadvantaged and vulnerable communities (DVCs). People in DVCs are more likely to be displaced by such extreme events and face greater obstacles to recover from them. There is little doubt that the impact of climate change tends to hit disadvantaged communities first—and worst.

Lengthy and extreme heat waves and cold snaps, massive storm surges, rising sea levels, and devastating wildfires are increasing in frequency and intensity, and the impact to populations is clear. But these events also impact labor markets, transportation routes, and vital utility infrastructure, often setting off a cascade of significant losses.

Each year, California battles blistering heat waves and devastating wildfires, shuttering businesses, destroying homes, and damaging supportive utility infrastructure. And in Florida, communities are still recovering from Hurricane Ian, which hit the Gulf coast in September 2022. Within hours of the storm’s landfall, energy grids across the state sustained catastrophic damage, leaving millions of people and businesses without power for days. Despite the state’s Public Service Commission investing billions to fortify its energy grid against storms, much of Florida’s grid assets will need to be rebuilt.

Pushing aging energy infrastructure to the brink

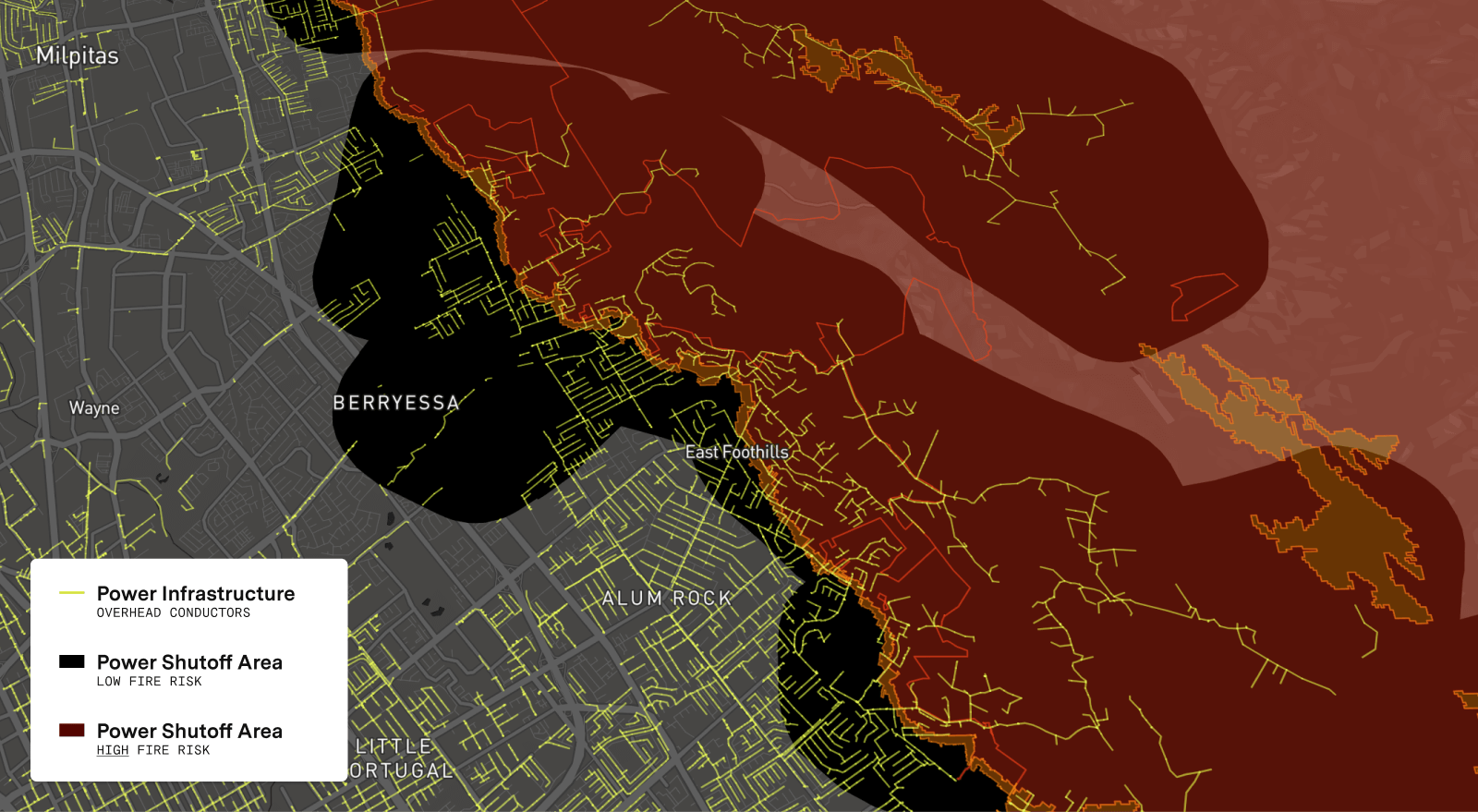

These extreme events are pushing aging energy infrastructure well beyond the point at which it was designed to operate, exacerbating impacts on the communities it serves. Due to the vulnerability of some electric grids, states attempt to protect energy infrastructure with planned power outages and calls for consumers to conserve energy. Heat waves in California in recent years have been long and intense enough to trigger the Public Safety Power Shutoff (PSPS) system, prompting rolling blackouts to help alleviate strain on the power grid.

In February 2021, a historic winter freeze in Texas forced the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT) to shut off the power supply to pre-empt the imminent collapse of a system unequipped to meet the unprecedented demand. The outage left more than 4.5 million energy customers without power in freezing conditions and resulted in hundreds of deaths. Like California, Texas also struggles to meet the demand for energy during conditions of extreme heat. An early season heat wave in May 2022 forced several power generation sites to go offline, an event that repeated itself throughout the intense summer.

In its current state, aging and vulnerable energy grids are less and less able to withstand increasing and unpredictable demands for reliable energy. As the effects of climate change continue to intensify, the impact of blackouts on communities across the board will become more consequential and dire—but especially for those that are vulnerable.

Climate events magnify existing vulnerabilities

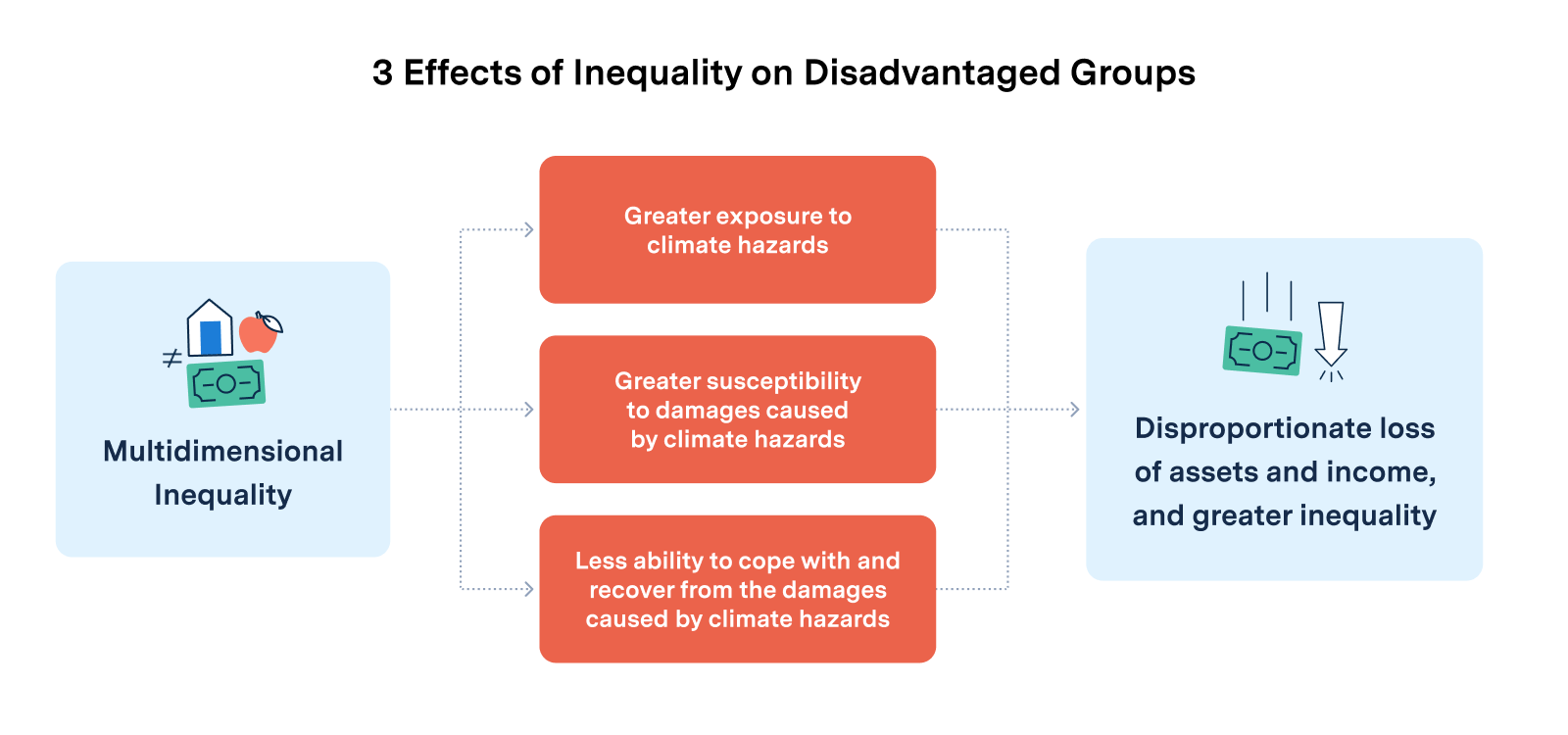

Disadvantaged groups already experience climate change more deeply due to the resources required to counterbalance the effects of extreme weather events. Energy usage, property restoration, and displacement impact their communities profoundly and disproportionately, exacerbating an already pernicious cycle of inequality.

- People in DVCs are more exposed to climate hazards. Research has shown that DVCs are more likely to be located in areas at a high risk of flooding, erosion, drought, heatwaves, and water scarcity. Certain occupations, typically filled by disadvantaged populations, perform duties outdoors, which can also increase their exposure to climate hazards.

- People in DVCs are more susceptible to damage caused by climate change. People living in exposed areas may experience greater damage not only due to environmental conditions, but also because the quality of housing construction may not withstand the effects of extreme weather events. Research has shown that even if their exposure is less, disadvantaged groups tend to suffer greater asset loss. People in DVCs are also more susceptible to health challenges related to climate change, such as asthma, water borne illnesses, and heat related illnesses.

- People in DVCs are less able to recover from climate change related damages. Recovering from climate related damages requires significant resources, whether that be in the form of time, access, or funds. People in DVCs are more likely to lack some or all of these resources. Exacerbating this disparity, low income renters are less likely to have renter’s insurance to ease the burden of catastrophic loss.

With each passing event, worsening inequality places disadvantaged groups at an outsized risk when energy grids fail, further exacerbating the impact of climate change on their communities. Throwing away a refrigerator full of food after a long power outage can have a significant impact on families and individuals on fixed incomes, fueling the cycle of inequality so keenly felt in DVCs.

Inequalities of the energy system

As damage to grids and communities becomes more frequent and widespread, regulators are beginning to acknowledge issues with energy affordability, grid vulnerabilities, and customer equity. Data is showing that more families are falling behind on electric and gas bills since the pandemic, and that as much as a third of the country cannot afford their electric bills.

As a result of pressure from consumer advocates and even state regulations, several utilities are starting to incorporate equity into programs and plans. California’s Clean Energy and Pollution Reduction Act directs agencies to take action on the many barriers low-income customers have with accessing clean energy. California is also taking the lead in requiring utility companies to implement percentage-of-income payment plans (PIPPs) to cap customer electric bills based on income.

Other states like Virginia, Massachusetts, Arizona, and Wisconsin are implementing similar efforts to improve equity in their energy systems. The Biden Administration’s Justice40 equity initiative has committed to funneling to DVCs at least 40% of the benefits from federal investments in clean energy. While considered a powerful force behind energy equality, advocates worry the funding will not reach vulnerable communities because of existing barriers that perpetuate inequalities. Utility commissions share in the challenges of implementing equity initiatives, pointing to the difficulty in reaching underserved customers as the primary barrier.

The role of geospatial data in identifying risk and vulnerability

DVC outreach is not the only challenge facing utility companies. As utilities work to update aging energy systems to withstand the forces of climate change, many are limited in their decision-making abilities by outdated processes used to evaluate the risk due to the severity and changeability of extreme weather events. Traditional engineering based assessments of load and capacity and historical weather data can no longer accurately predict risk or even begin to assess a community’s resilience.

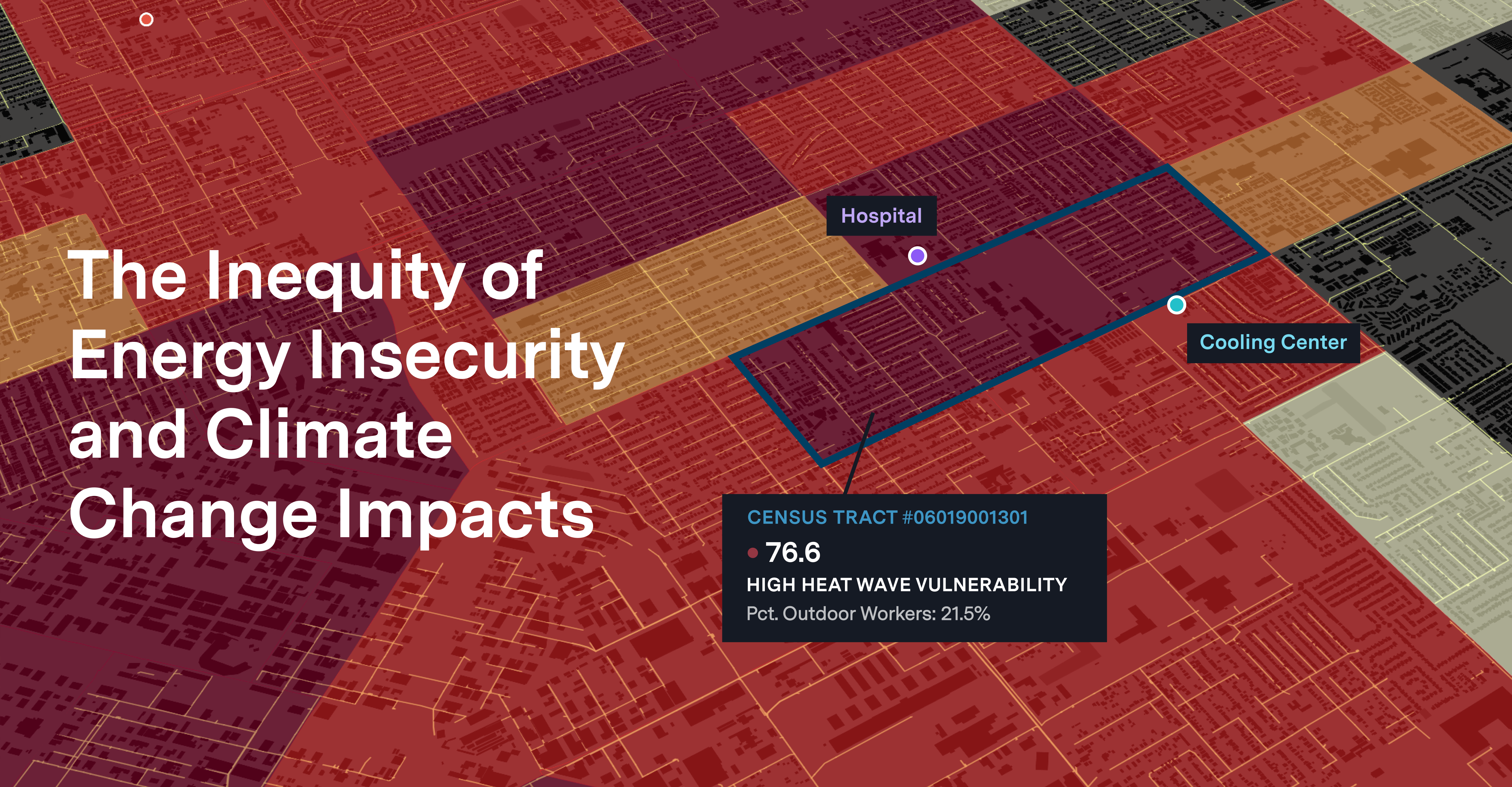

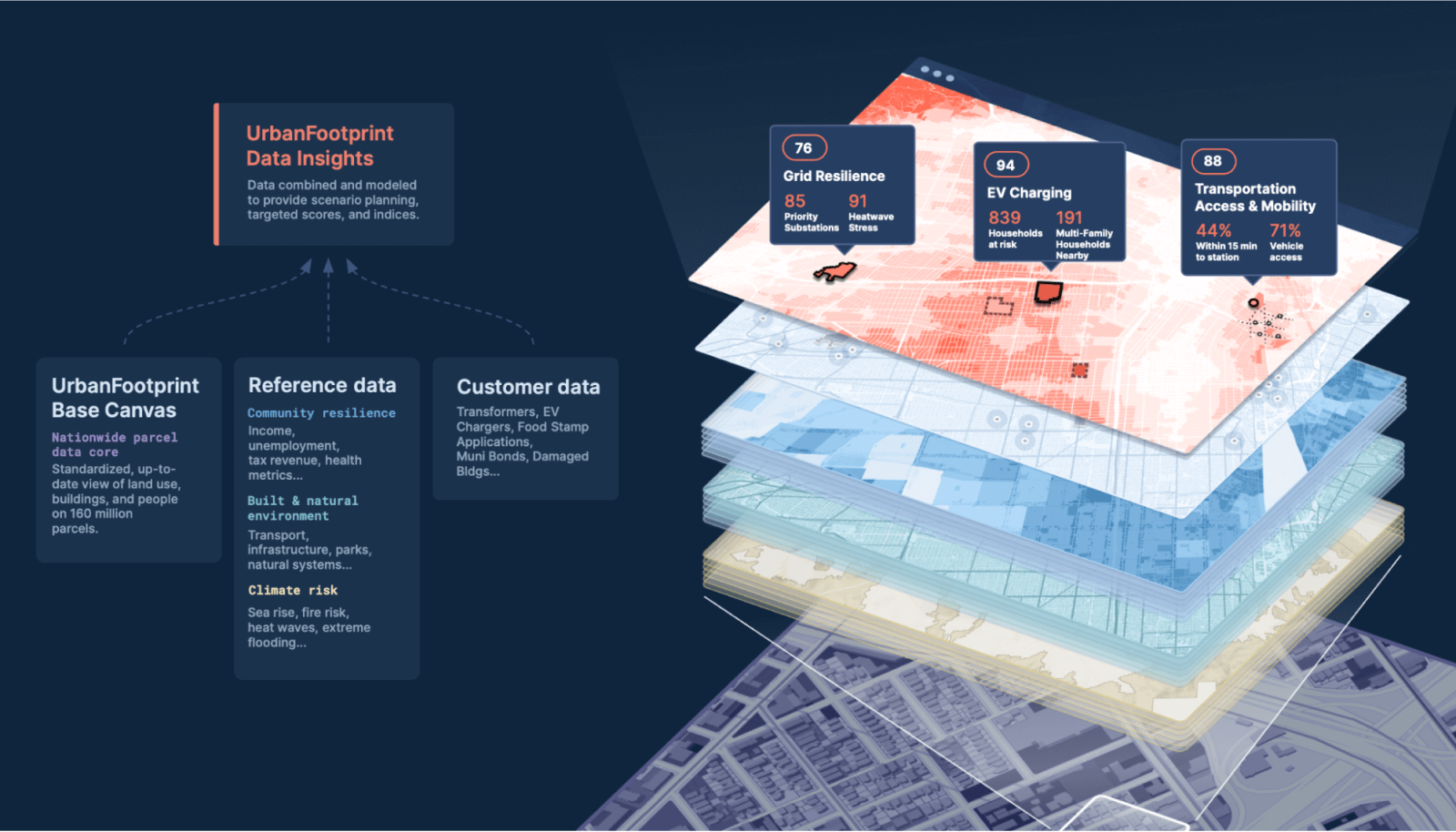

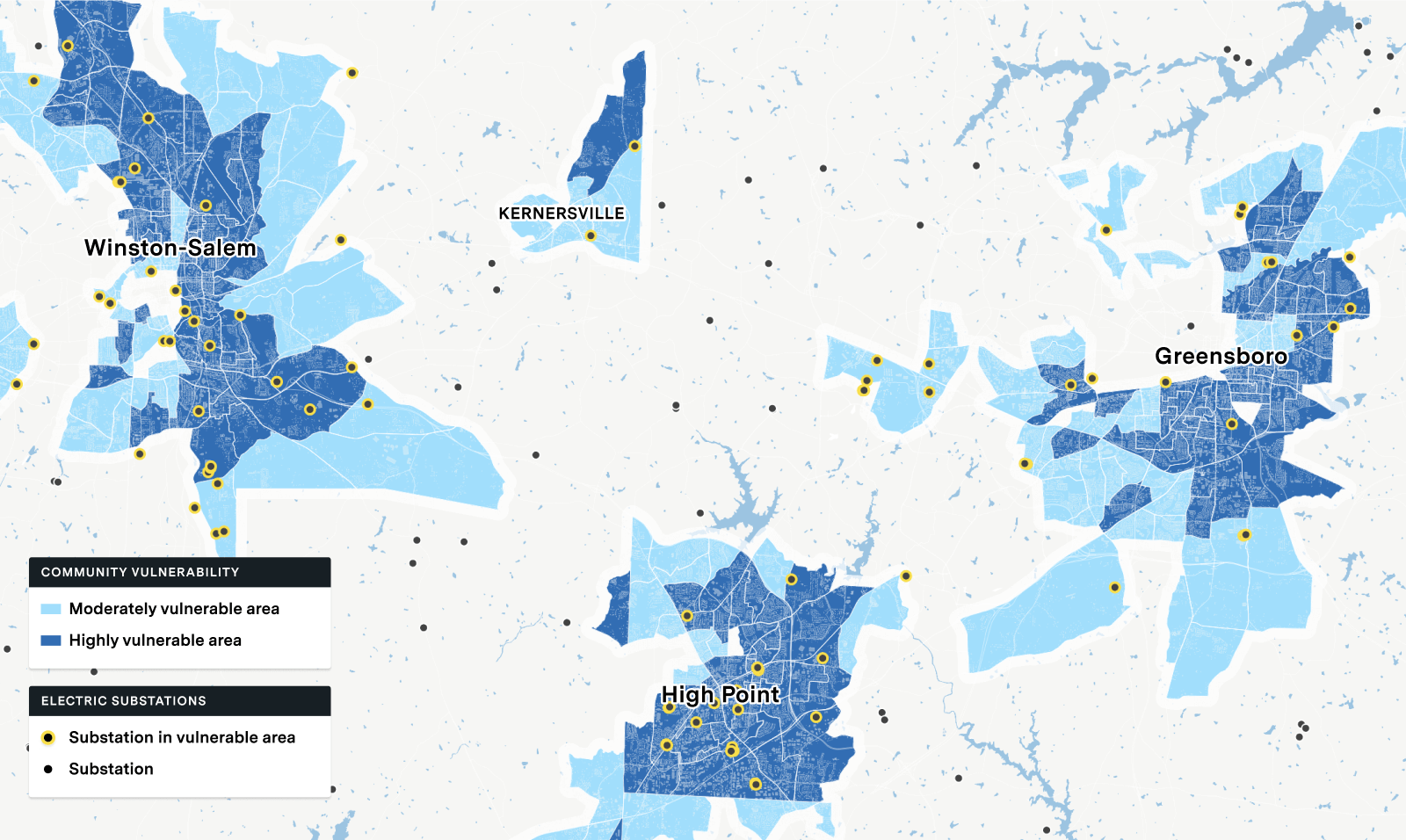

Identifying vulnerabilities of a service population, especially those that are disadvantaged, is a critical step to equitable energy systems. But to do that, energy providers must analyze datasets on multiple factors, including economic stress, social vulnerability, natural hazards, and climate risk, and then understand how many of these factors interact.

UrbanFootprint’s visual mapping capabilities allow energy providers to analyze the intersection of these otherwise independent datasets, empowering them with a more holistic approach to identifying vulnerabilities. Finding relationships in the data can help utilities plan scenarios, make critical infrastructure decisions, and mitigate risks to both power grid assets and the communities surrounding them. Not only can actionable insights guide decisions on infrastructure investments, but geospatial data can map the risks of natural hazard events, especially those exacerbated by climate change.

Using geospatial data insights to boost resilience in DVCs

Having such a comprehensive, relational view of urban, social, climate, and infrastructure factors enables utilities to prioritize spending for DVCs. Some examples of such geospatial data insights at work are:

- Prioritizing grid resilience in areas where low-income seniors are clustered

- Siting of cooling centers in locations that are accessible to those most vulnerable

- Building backup battery storage behind meters to account for high fire risk days

- Mapping medically dependent populations and cross-referencing that with outage data

- Assessing optimal sites for EVs to ensure infrastructure meets equity goals and new state, local, and federal requirements

- Locating down to the parcel level where to target energy programs to best serve residents

With advancements in the area of data mapping and analytics, energy providers, grid planners, and climate resilience groups can be better equipped to face the challenges of climate change equitably. A unified, data-driven platform with the ability to layer multiple datasets is key to understanding the relationship between energy insecurity and climate change.

Reach out to our energy team to learn more at adapt-better@urbanfootprint.com.