Picture a family without enough to eat. What images come to mind? If you imagine someone in your own community, you’re probably right. Our data shows that approximately 15.5 million people are currently living with food insecurity, worrying about affording food, unable to pay for healthy meals, or cutting back on portions so there’s enough to go around. That’s a population bigger than the entire state of Pennsylvania.

The fact is, food insecurity affects every state in the nation. It can be long term or temporary, and its effects are often devastating.

What is food insecurity?

The U.S. Department of Agriculture defines food insecurity in America as “the limited or uncertain availability of nutritionally adequate and safe foods, or limited or uncertain ability to acquire acceptable foods in socially acceptable ways.”

In other words, people experiencing food insecurity in America:

- Worry they will run out of food before there is money to buy more

- Can’t afford balanced meals

- Skip or reduce the size of meals because they struggle to make ends meet

- Eat less than they feel they should — even when they’re hungry — because of money concerns

- Lose weight because they can’t afford to keep food on the table

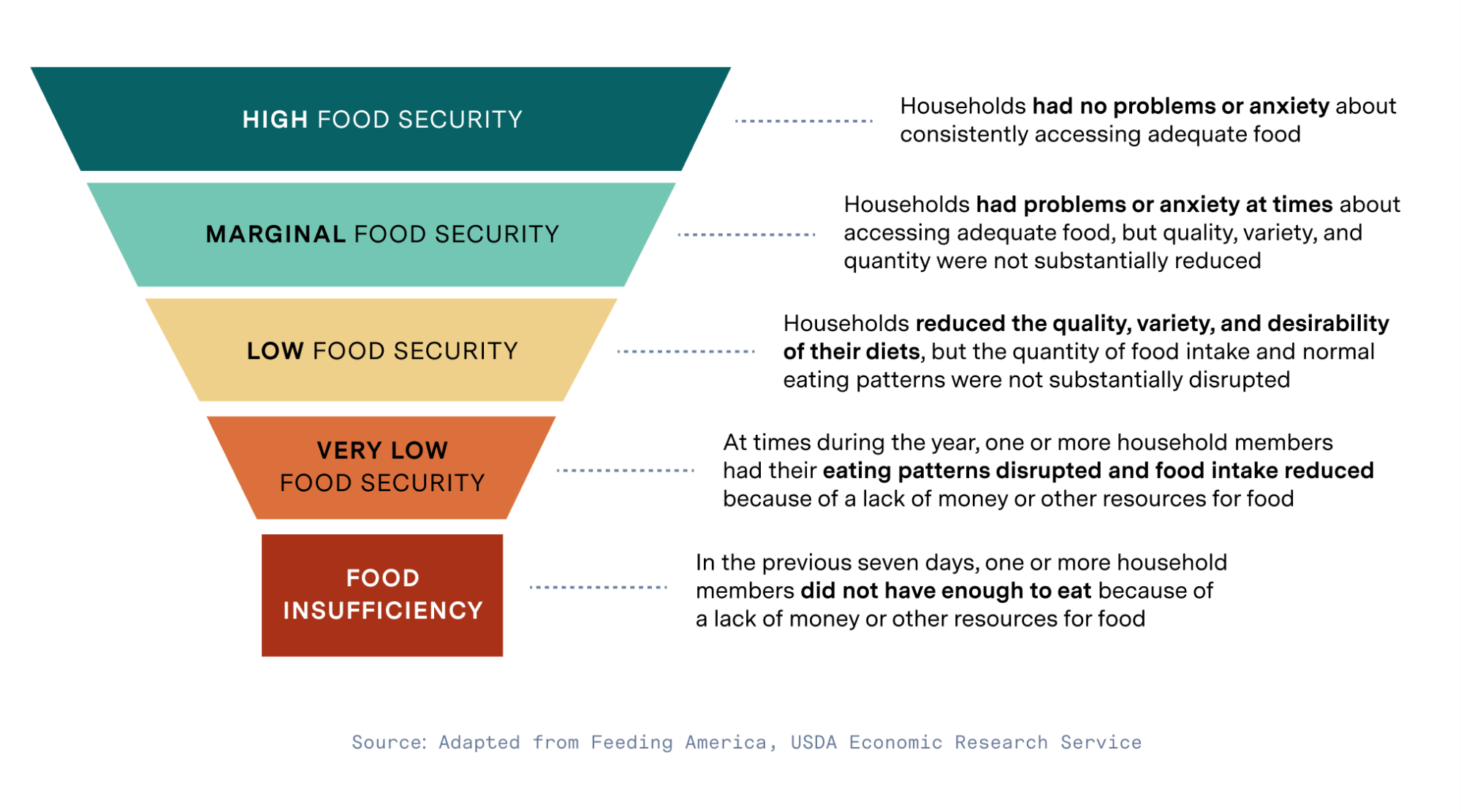

Food insecurity in the United States is classified at two levels:

- Low food security describes households that typically don’t report cutting back on their intake, but do experience reduced variety and quality of food.

- Very low food security describes households that cut back on the amount, quality, and variety of foods they eat.

Many people who struggle with food insecurity also face food insufficiency, a more extreme state defined as not having enough food to eat sometime in the last week. Our research found that in October of 2021, more than 70% of households that reported experiencing food insecurity also reported food insufficiency.

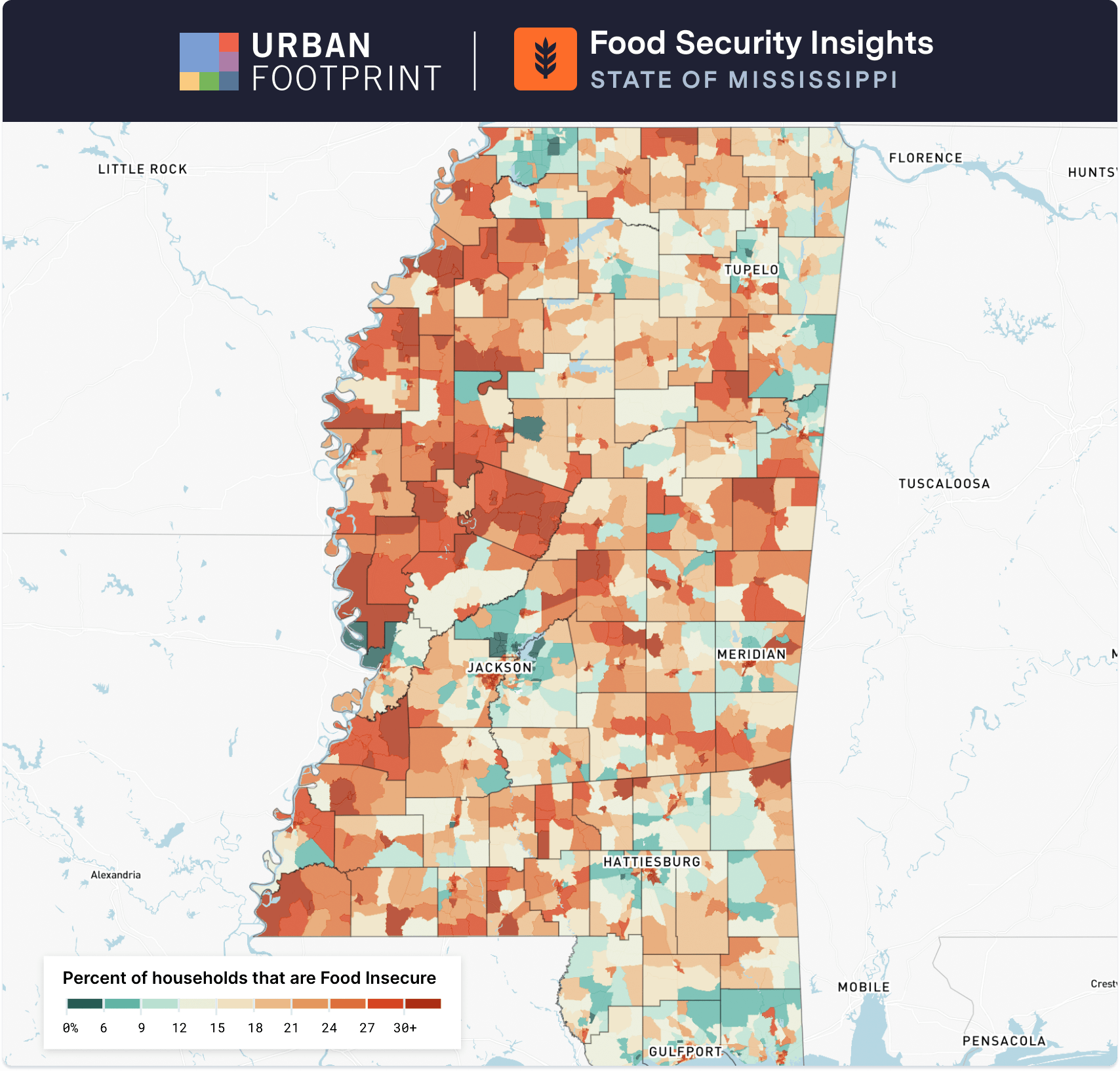

Overall, food insecurity rates in America vary widely among states, depending on the characteristics of their populations, availability of social services, and economic health. Households in the South and Midwest are more likely to experience food insecurity than those on the coasts. In some of the most food insecure states in the nation — Mississippi, Louisiana, Texas, New Mexico, and Oklahoma — more than one in five households is food insecure.

How does the U.S. government measure food insecurity?

The USDA measures how many households experience food insecurity and how severe are the shortages they face through an annual survey conducted by the agency’s Economic Research Service (ERS).

The survey looks at a variety of factors to identify food-insecure households, including: whether everyone in the family has enough to eat; whether they have enough of the different kinds of food the household wants to eat; and whether people in the family experience anxiety about food running out before there is money to buy more.

In 2020, the ERS surveyed 34,330 households, a representative sample of the United States’ 130 million households. If people reported three or more food insecurity conditions, they were classified as “food insecure.” Of the 13.8 million households struggling with food insecurity, 2.9 million — a population the size of Kansas — had children at home. Between 2019 and 2020, food insecurity in America rose in all households with children — but especially among Black families and households in the South.

What causes food insecurity?

Let’s take a look at what causes food insecurity and why it has been on the rise over the past few years. Like many complex issues, hunger is an issue where an array of factors comes into play.

Clearly, people’s income and employment are the biggest drivers for whether they can afford to keep food on the table each day. But it’s important to look deeper than earnings alone. The fact is that in the United States, demographic factors such as race and ethnicity have a lot to do with how much a working person earns, and by extension, how easy or hard it is to pay for necessities like groceries.

Government statistics back this up, with Black and Latino households disproportionately more likely to have trouble keeping food in the cupboards. Feeding America projects that in 2021 one in five Black people may experience food insecurity, compared to just over one in ten White individuals.

Because peoples’ income also influences where they can afford to live, your neighborhood can also affect your access to affordable, nutritious food. For example, rural and urban dwellers alike may struggle to get to a full-service grocery store — leaving them to rely on convenience stores or fast food. Picture being a parent of young children or a person with a wheelchair: without your own car or public transportation, you’d have to rely on family or friends to keep your household fed.

However, even in places with ample food-buying options, people who struggle to make ends meet will always be at higher risk of food insecurity. For many, an unforeseen emergency or health crisis, especially for those without health insurance, can force people to choose between paying bills or buying groceries. When you are living on a limited income, events like losing a job, taking in an elderly relative, or even a modest increase in rent can tip the delicate balance from getting by to going without.

What are the effects of food insecurity?

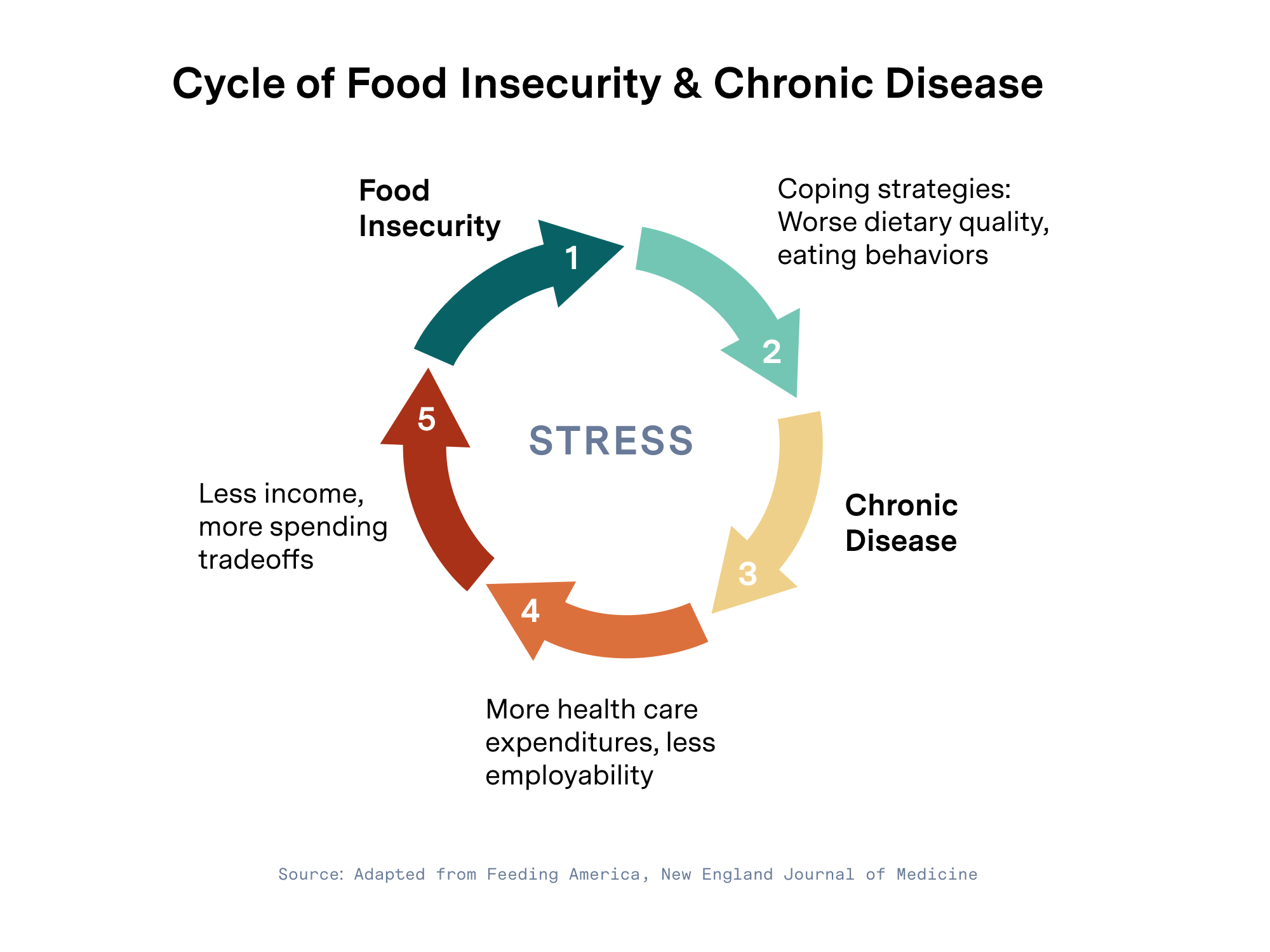

Food insecurity takes a serious toll on people’s health, well-being, and quality of life. When you have no choice but to rely on cheap, less nutritious foods, you’re at greater risk of life-threatening health complications like diabetes, heart disease, and high blood pressure. A recent study found that older adults not receiving food assistance had more hospital and long-term care admissions as well as emergency room visits — costing an extra $2,360 per person annually. And when money is tight, families forced to choose whether they can afford food or medicine have no good options: pay for groceries and let their health deteriorate, or pay for treatment and go hungry — which restarts the cycle all over again.

It’s not surprising that the stress of living with food insecurity can have long-term consequences for people’s mental health, which can kick start its own problematic pattern.

With stress levels high and not enough to eat, it’s harder to hold down a well paying job. And without a steady income, food insecurity can go from bad to worse.

Importantly, children are especially vulnerable to the effects of food insecurity. Research has strongly suggested that even mild food insecurity significantly affects their development, increasing their risk of developmental delays, cognitive impairment, unhealthy weight, poor grades, and impaired social skills.

COVID and food insecurity in America

Unsurprisingly, the seismic upheavals brought by COVID-19 spurred an increase in the number of food-insecure households in America. Before the start of the pandemic, overall food insecurity in the United States had reached its lowest point since measurement began in the 1990s. But as unemployment soared, demand at food pantries across the country rose sharply. Earlier this year, we found that between March 2020 and March 2021 the number of households across the U.S. facing food insecurity had risen by 45%. This trend is likely to continue, with rising food prices and a looming housing crisis.

Children were particularly affected by fallout from COVID-19. The shift to remote learning in many districts was correlated with an increase in food insecurity in children who relied on getting free or reduced-price meals at school. One report from the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health noted that the percentage of U.S. households with children who were food insecure doubled in 2020, from 14% to 28%, with communities of color affected the most.

It’s important to remember that economic recovery from the pandemic does not mean food insecurity in the U.S. will end, especially for those who are disproportionately affected by it. Consider that in 2019 more than one in three households with incomes below the poverty line and nearly one in three single-mother households experienced food insecurity.

What can we do about food insecurity in America?

In addition to the nation’s non-profit and charitable efforts to address food insecurity, a variety of federal policies and programs are aimed at remedying food insecurity in America.

- The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), which provides assistance to supplement the food budget of needy families so they can purchase healthy food. SNAP is a huge program, totaling $85.6B in 2020.

- The Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC), which provides federal grants to states for supplemental foods, health care referrals, and nutrition education for low-income pregnant, breastfeeding, and postpartum women, as well as to infants and children up to age five who are at nutritional risk. In 2020, $4.9B was spent on WIC, with states receiving approximately $65 million on average.

- The National School Lunch Program is a more than $10B program which operates in public and non-profit private schools and residential child care institutions, providing nutritionally balanced, low-cost or free lunches to children each school day.

- The School Breakfast Program is a $3.6B program which provides reimbursement to states to operate nonprofit breakfast programs in schools and residential childcare centers.

Despite the significant spending that goes into these programs, and the additional resources the federal government has allocated over the past year to help Americans at highest risk of food insecurity, the neediest households aren’t always getting the help they need. Nationally, participation in these programs is uneven, and not all individuals who are eligible for the programs are enrolled.

One recent study found that while the Biden administration’s new child tax credit was successful at reducing food insecurity, more than 40% of families with incomes below $25,000 reported they had not received the payments. As a result, researchers believe that the program is currently delivering only about half of its potential benefit.

Through working government agencies, food banks, and community based organizations, we’ve found that improving these outcomes requires overcoming three distinct challenges:

- Identifying the extent of need: expanding food relief funds and resources to meet growing demand

- Mapping and allocating resources to meet the need: using up-to-date information to target food relief to those who would benefit

- Closing gaps between need and relief distribution: reaching and serving those in need who are unaware of programs or cannot access them via standard channels

The fact is, when it comes to understanding and addressing food insecurity in America, data matters. With accurate, timely insights into people’s needs, governments and relief organizations can more effectively target their services, reach those who aren’t applying for them, measure the success of that outreach, and ultimately work more effectively together.

How is UrbanFootprint helping in the fight against hunger?

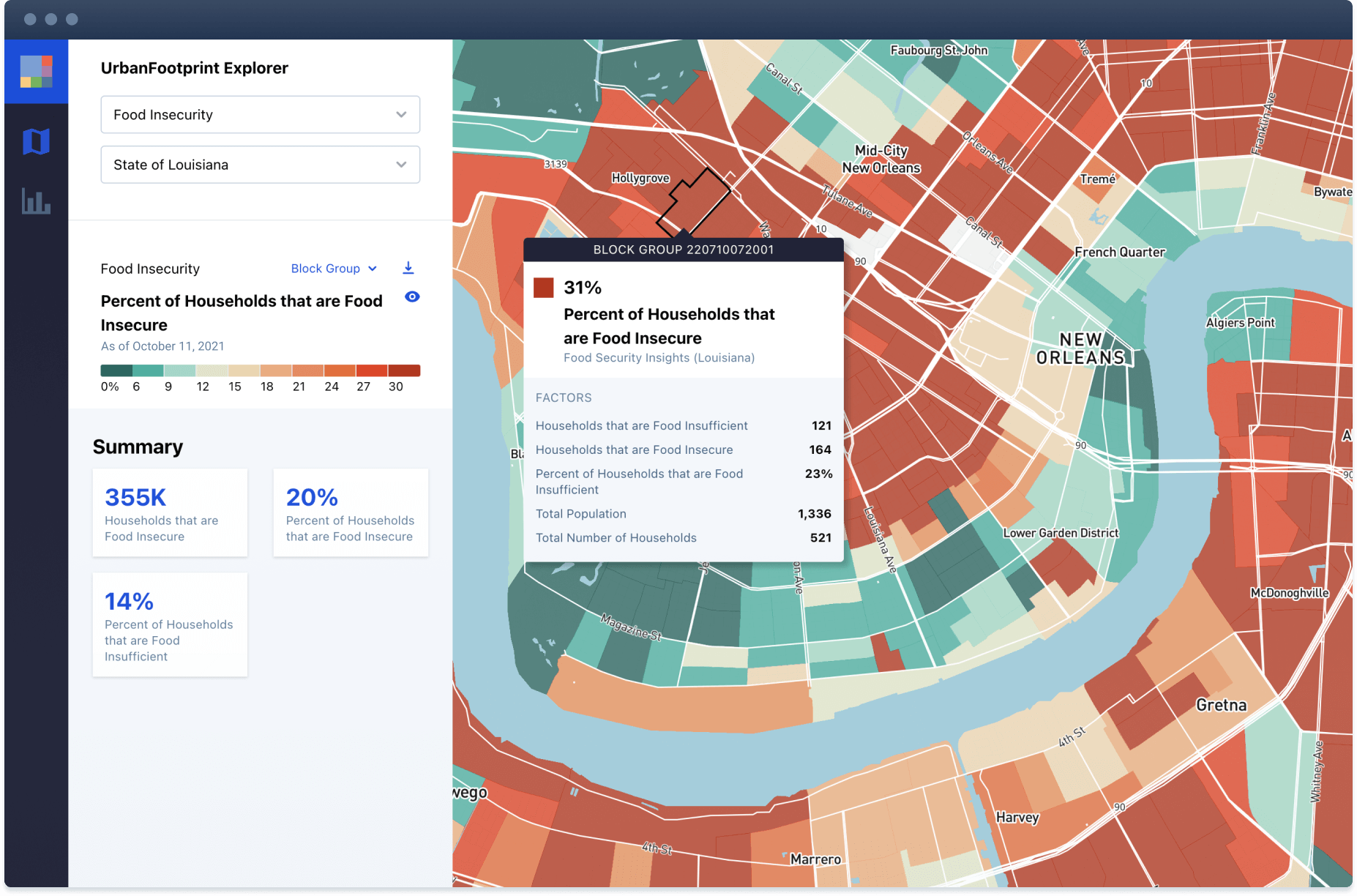

Earlier this year, UrbanFootprint worked with partners in Louisiana to develop Food Security Insights (FSI), the first-ever dynamic data product developed to track the scale and distribution of the evolving food security crisis across the country. FSI data are updated every two weeks with estimates down to the census block-group level, enabling state and local agencies to identify communities with the greatest need and the lowest levels of enrollment in programs like SNAP and WIC. Public and nonprofit entities can then target households in these areas through online or in-person campaigns to encourage enrollment. FSI data are also used to coordinate activities between local food banks, and to advocate for better federal and state hunger relief policies and programs.

Retail companies have long used data-driven methods to better understand, connect with, and target consumers. Now it’s time to put similar technologies and practices to work in the fight to end hunger in the U.S.