A new era in the fight against hunger

In September of this year, the White House held the second ever Hunger Conference, and with it committed $8 billion to end hunger and reduce diet related diseases by 2030. The first Hunger Conference, held in 1969, inspired two foundational steps in the fight against hunger: first creating food stamps (now known as the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program, SNAP), followed by the Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) program in 1972 . Over the last fifty plus years, these programs have helped millions of families to meet basic nutritional needs.

The renewed and ambitious White House initiative has the potential to positively impact millions of additional Americans and their communities. But money alone will not meet these goals – governments and their community partners will need the right tools to catalyze action and spend these funds effectively.

Five pillars for partnerships

The White House’s goal is to bring food assistance programs into the digital age to meet modern standards for health and equity. More than a quarter of the administration’s commitment is focused on innovative ways to serve those in need. $2.5 billion will be invested in start-ups pioneering hunger and food insecurity solutions, with an additional $4 billion earmarked for philanthropic groups.

Solution providers and nonprofit organizations will focus on five pillars:

- Pillar 1 – Improve Food Access and Affordability

- Pillar 2 – Integrate Nutrition and Health

- Pillar 3 – Empower Consumers to Make and Have Access to Healthy Choices

- Pillar 4 – Support Physical Activity for All

- Pillar 5 – Enhance Nutrition and Food Security Research

The time is now to evaluate new approaches to solving long-standing problems.

Who benefits from food assistance programs?

A through-line for each pillar is understanding who is most at risk for food insecurity. As the conference highlighted, hunger and nutrition are not experienced equally across the country, and are part of larger health concerns for many people. Because of this, predicting or identifying where hunger is felt most deeply is difficult to do without a wealth of information. Blanketed outreach, therefore, should be better targeted through granular community data and integrated eligibility models to serve those individuals most in need.

Children

Roughly 1 in 4 children in the US participate in SNAP, and represent nearly half of all program recipients. Children have long been the primary demographic for combating hunger, and today, children of color and multi-generational households are at highest risk.

The national school lunch program dates back to 1947, and has been buttressed by school breakfast programs since 1966, but these programs today face basic challenges such as working scratch kitchen facilities and resource staffing.

Without these programs, children face compounding long-term negative effects. Undernourished and food insecure children are more likely to underperform academically, and often exhibit negative behaviors in the classroom that can impact college and employment opportunities. This can lead to generational cycles of food insecurity and economic instability.

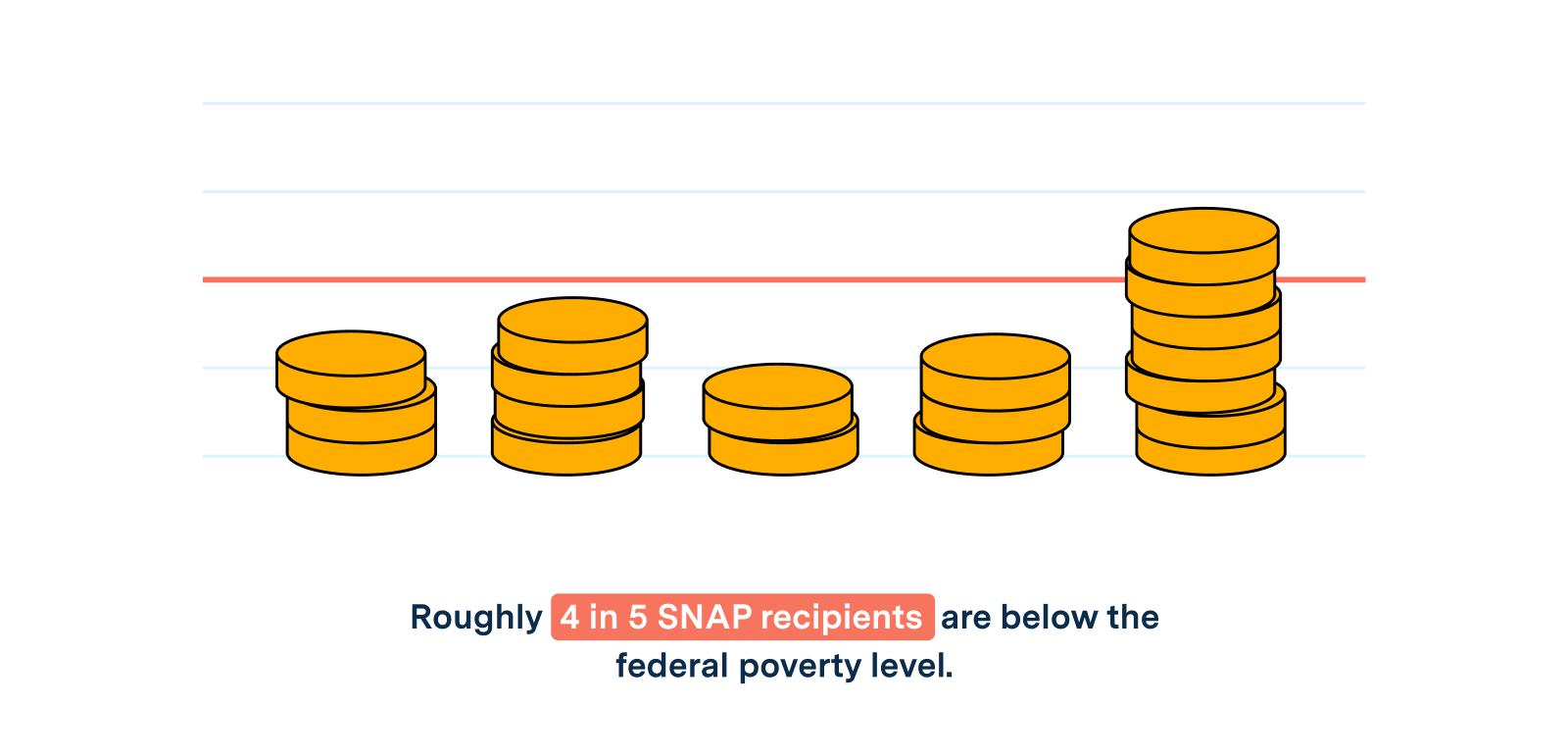

Poorest Americans

Roughly 4 in 5 SNAP recipients are below the federal poverty level. This number is particularly high in rural populations and in communities of color. Rates of obesity and chronic diabetes are higher than average in these communities as well, which is not solely a health matter, but tied closely to one’s diet.

SNAP is a critical tool for helping these communities meet basic living and health standards. Roughly 10% of recipients are able to move out of poverty thanks to the program, and another 10% move out of extreme poverty. The White House’s initiative additionally focuses on increasing healthy options that can fight food related diseases, which can reduce certain healthcare costs in the long run.

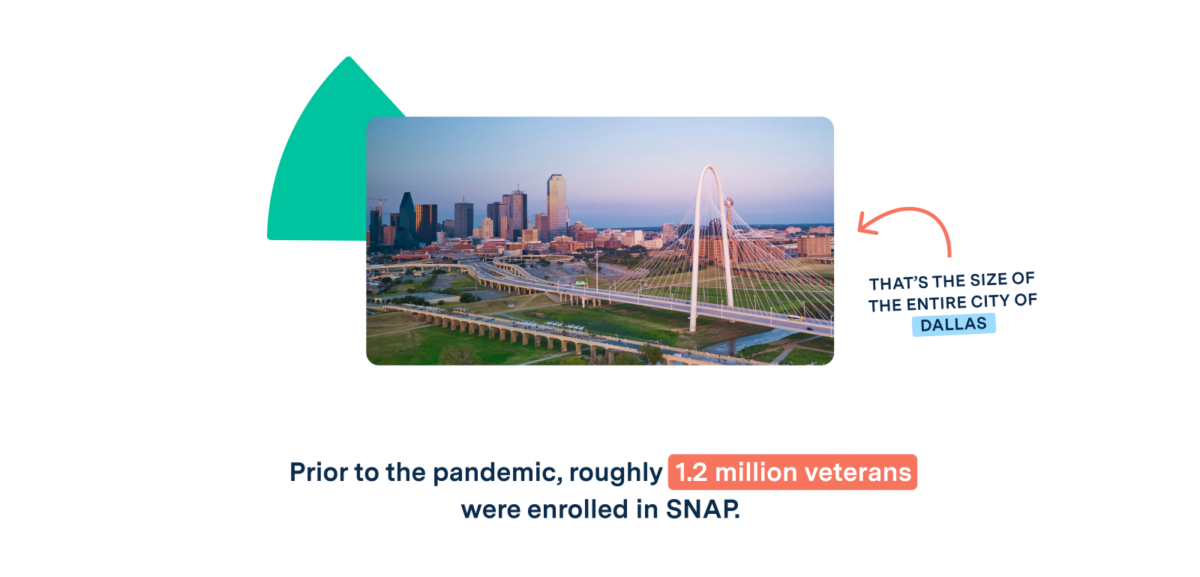

Veterans

Prior to the pandemic, roughly 1.2 million veterans were enrolled in SNAP. That number could be on the rise with the expiration of emergency services. Food assistance is critical for veterans who suffer from multiple post-duty challenges, which includes 2 of 5 claiming a service related disability that can affect their employment rates and medical expenses.

Veterans also experience higher rates of homelessness than the general population, which presents challenges for outreach programs to ensure consistent delivery of food services for individuals that lack permanent addresses.

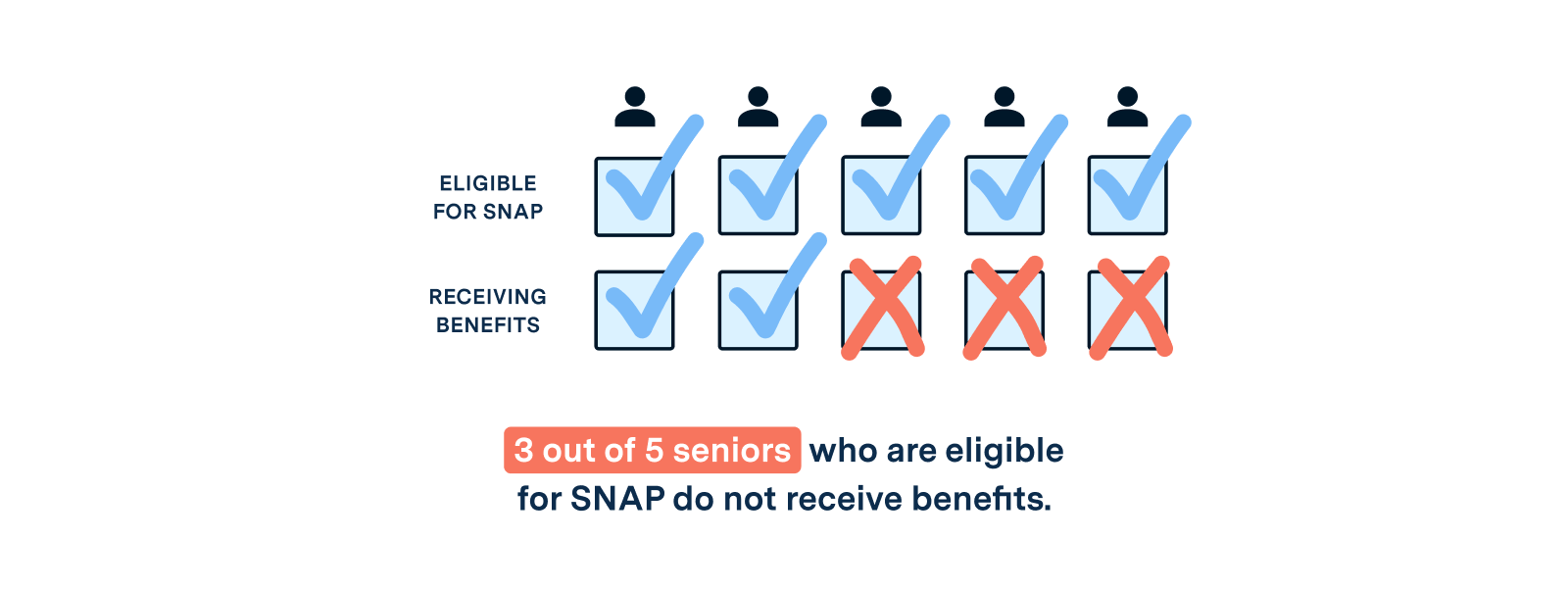

Seniors

Nearly 5 million seniors (60 years of age or older) are enrolled in SNAP, but that represents just 40% of eligible individuals. That means that 3 out of 5 seniors who are eligible do not receive benefits, which can put them in risky nutritional and health situations.

Filling this meal and benefits gap is critical for many senior households that are likely unaware there is assistance available to them. With rising inflation, this problem is worsening and educational outreach is critical.

Learning from COVID era exemptions

Despite clear evidence showing the positive impact of food assistance programs, federal funding and state resources are not guaranteed. Temporary measures during the COVID-19 pandemic provided flexibility for outreach programs to provide for their communities, but those adjustments are expiring. Many households remain in unstable economic, food, and health statuses, meaning people who were protected by continuous emergency services are once again at risk of churning, or losing their eligibility status.

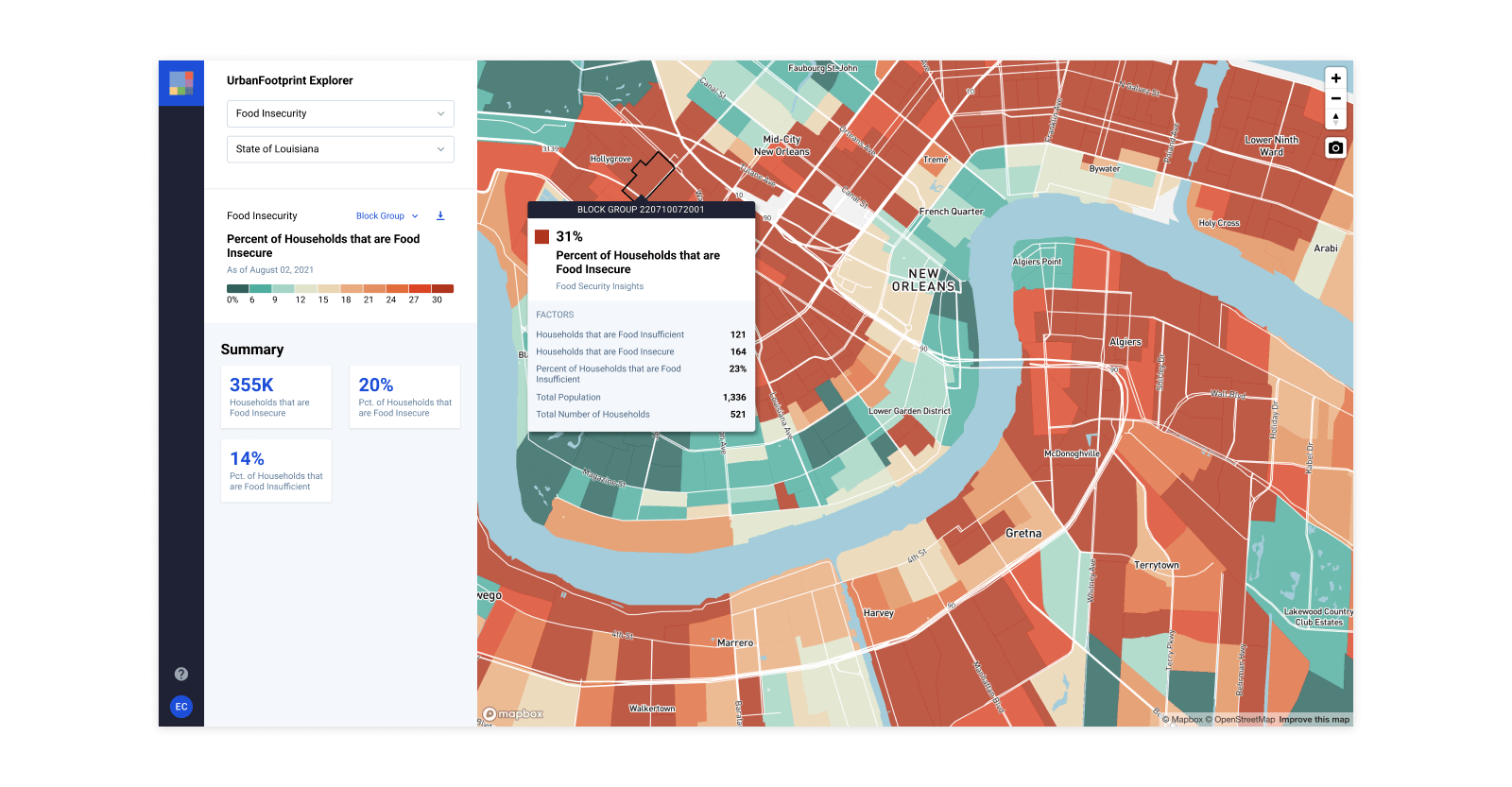

We have an opportunity to learn from this experience. Historic meal-gap information has served as a great starting place for organizations trying to understand where their underserved communities were located, and emergency community data over the past few years shined greater light on at-risk households. But, this retrospective approach must be complemented by real-time updates to ensure actionable insights and effective community engagement.

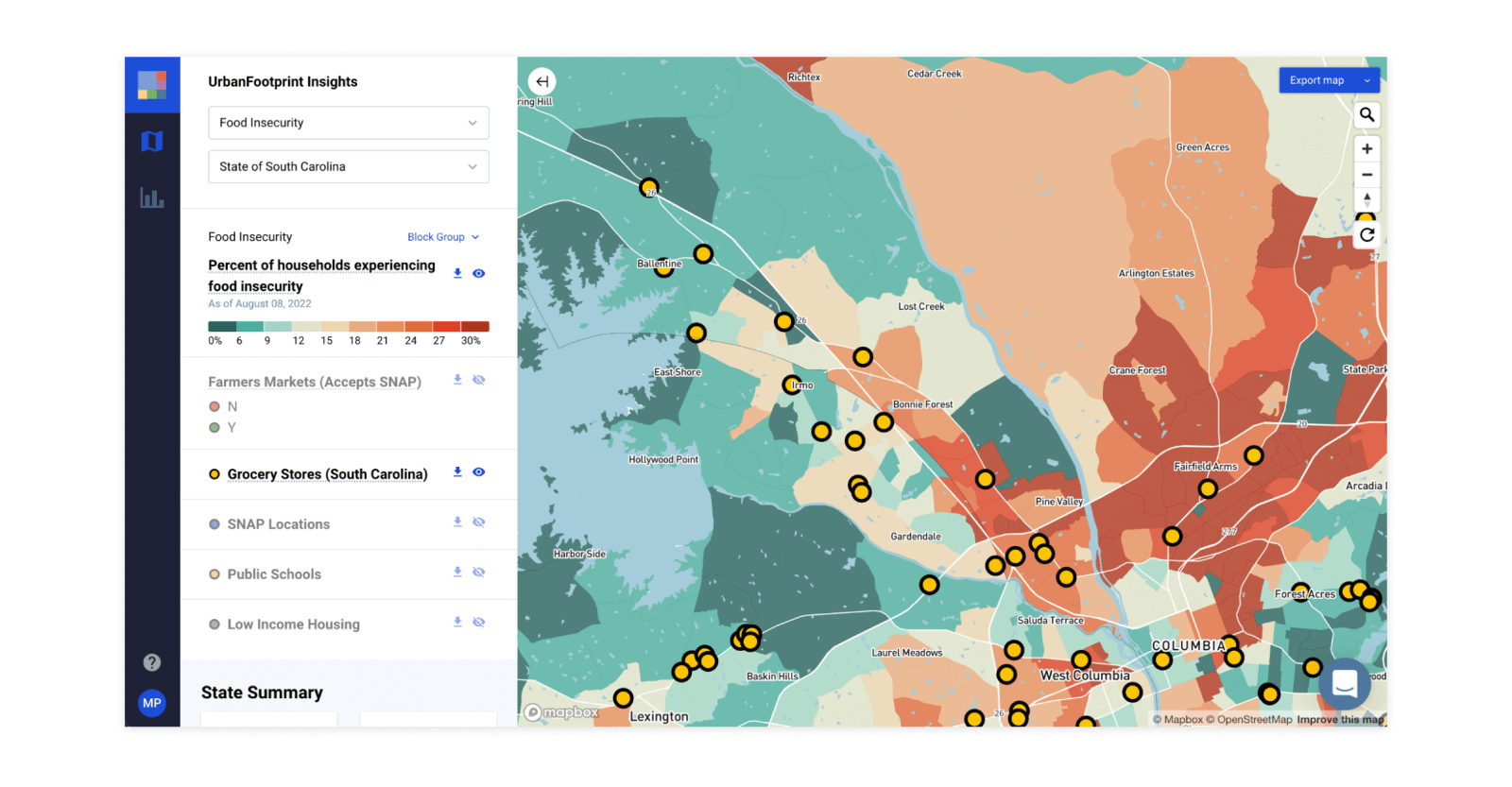

UrbanFootprint created an innovative Food Security Insights platform to track recovery during the pandemic as well as drive the fight against hunger in the future. Through regularly updated community data and need-based algorithms, local governments, food banks, and their partners can identify and quantify where assistance is needed most, and prioritize their efforts on servicing those communities.

Given the ever-evolving state of hunger, states must gain clear visibility into the number of households eligible and in-need of assistance. Proactive states can partner with solution providers to identify this population, compare it to program enrollment, and ensure that enrollment gaps are minimized and eligible individuals are reached in time.

Empowering local community partners

No one knows their vulnerable and at-risk populations more than the countless volunteers and personnel that deliver food to these communities, day in and day out. From churches and schools, to food banks and soup kitchens, these local stakeholders are at the frontline fighting hunger.

Empowering these groups with granular data insights will take the slow analogue guesswork out of their operations, allowing them to focus on what they do best with their community partners on-the-ground. Sharing information and data in a single platform can expedite planning, reduce confusion or redundant work, and ensure that all stakeholders have the information they need to service their communities faster and more effectively.

Public-private partnerships are necessary to meet the ambitious goals laid out by the White House and take strides toward ending the hunger crisis. Every moment that is freed up through technological or data insights is a moment that programs can directly provide services to their communities.