An Analysis of California Assembly Bill 2011

In collaboration with Ian Carlton (MapCraft), Jason Moody (EPS), and Lewis Knight

Executive Summary

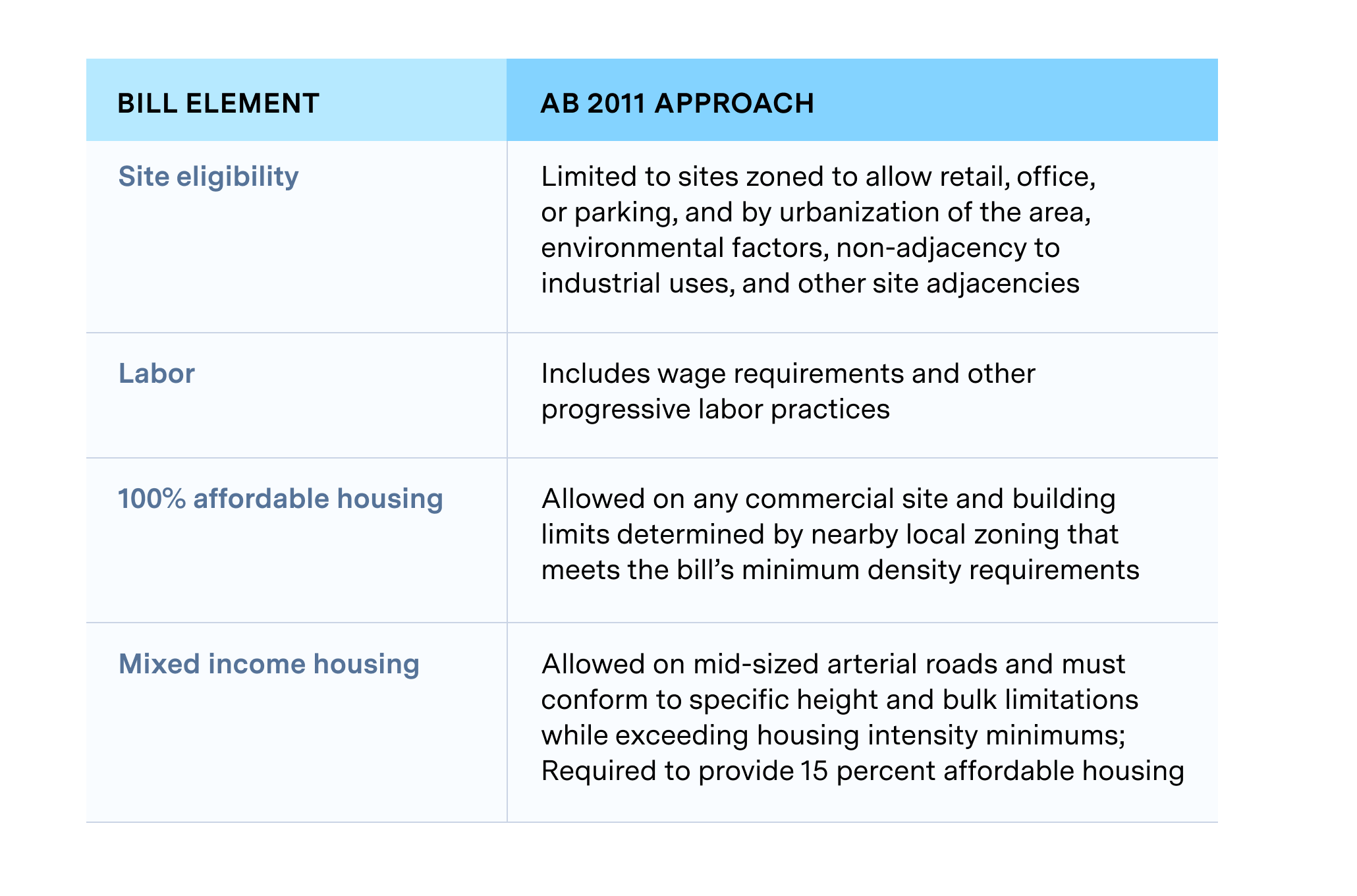

California’s recent legislative sessions have seen a range of housing policy proposals aimed at confronting the state’s ongoing housing challenges. A number of bills have focused on converting underutilized commercial property as a way to close major housing production gaps, including 2020’s AB 3107 (Bloom), SB 1385 (Caballero), and AB 2580 (Eggman) that inspired 2021’s SB 6 (Caballero), AB 115 (Bloom), and SB 15 (Portantino). In the 2022 legislative session, AB 2011 (Wicks), builds on these bills. AB 2011 requires high road labor practices and adopts two distinct provisions to facilitate infill housing on commercial lands. The first provision allows ‘as of right’ housing development in all commercial zones within urban districts for projects that are 100% affordable to lower income households.

A second provision hones in on underutilized strip commercial corridors and allows housing development on commercial lands that front arterial roadways, as long as the development meets specific mixed-income targets and a host of other objective criteria. AB 2011 sets specific standards for infill location, minimum density, maximum height, and urban design and grants projects streamlined approval based on meeting these specific objective development standards. The bill does not allow demolition of existing housing, adjacency to industrial uses or freeways, or development on environmentally sensitive areas. This study quantifies the various outcomes and benefits of the mixed income portion of the bill. While additional 100% affordable projects will result, they are not included in the quantities and analysis that follows.

UrbanFootprint, HDR/Calthorpe, Mapcraft Labs, and Economic & Planning Systems collaborated to evaluate the potential outcomes and impacts of AB 2011’s commercial corridor and TOD provisions. These provisions specifically streamline development approval for housing production on urban commercial corridors so long as at least 15% of a project’s new units are affordable to lower income renters or buyers. In addition, the law requires that all construction workers building this housing be paid prevailing wages and provided health care and apprentice training opportunities.

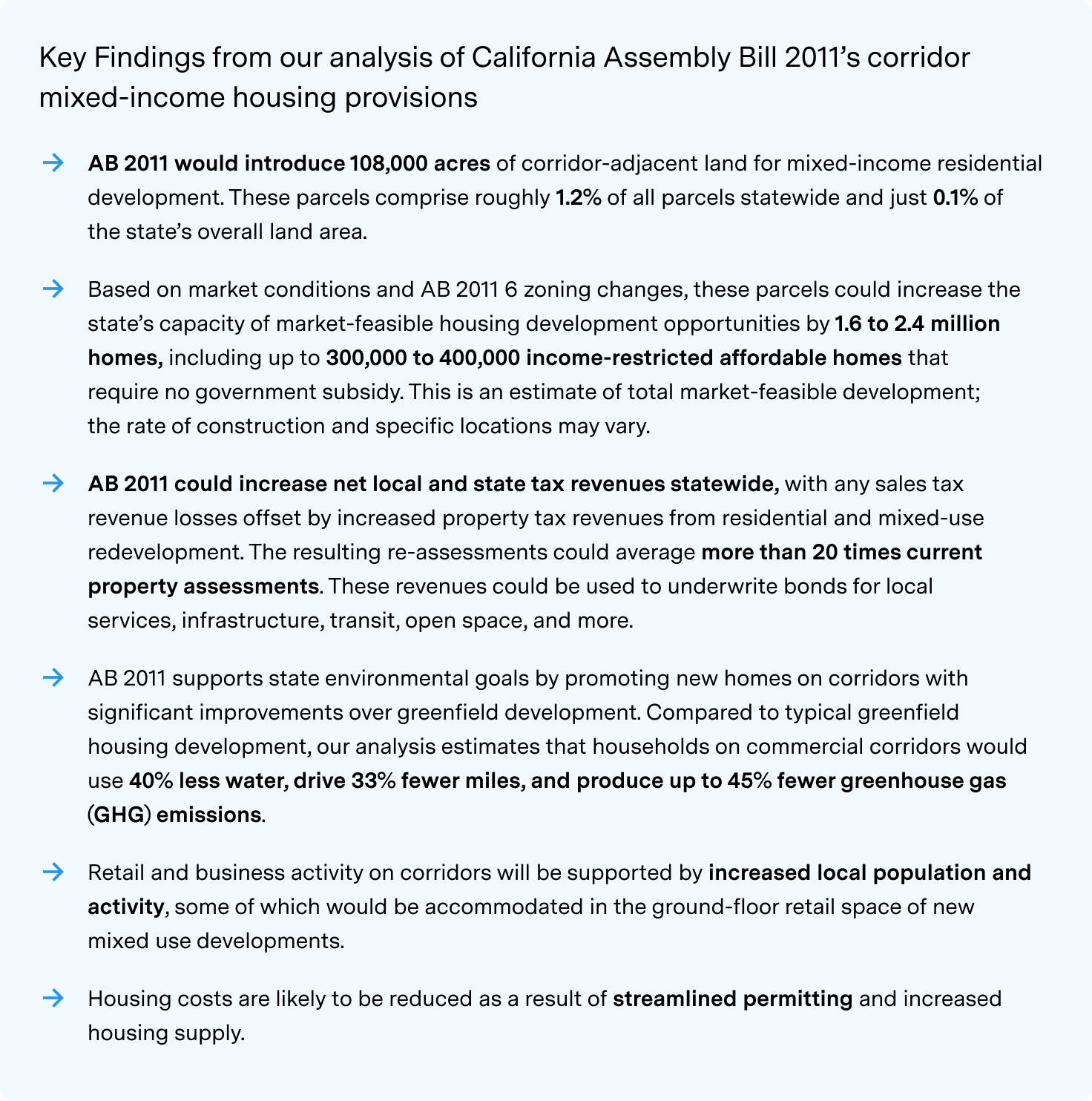

Our analysis estimates that strip commercial properties eligible under the bill’s mixed-income corridors provisions could increase market-feasible housing development opportunities across California by 1.6 to 2.4 million new homes. If realized, such housing production would deliver accessible affordable housing options, contribute substantial property value to tax rolls, and provide significant environmental and natural resource benefits in areas that are currently underutilized.

Introduction

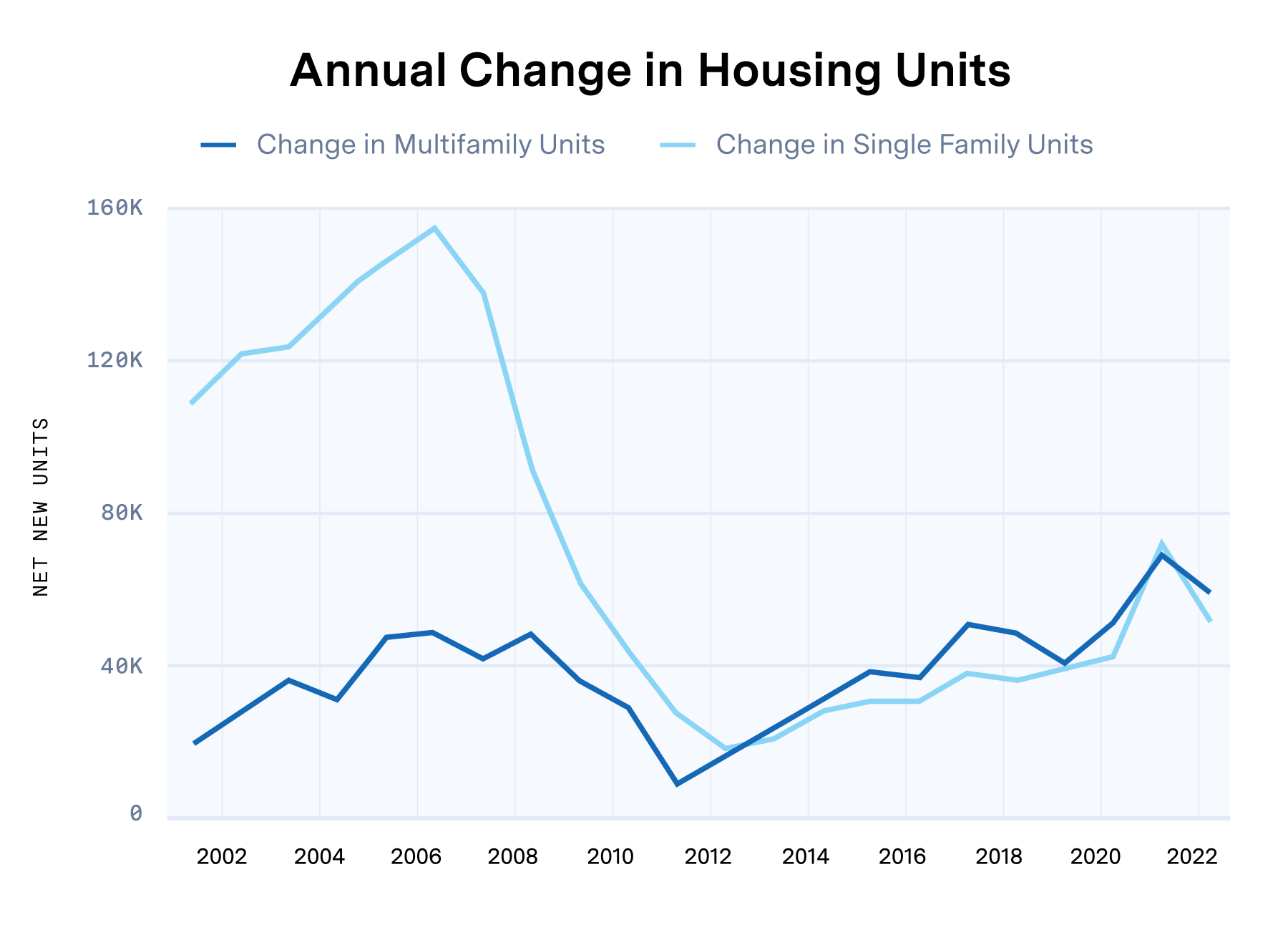

California is in a housing crisis. The median price of a single-family home exceeds $800,000, and over half of renters – including 80 percent of low-income renters – are paying more than 30 percent of their income toward housing. In 2020, over 160,000 Californians experienced homelessness on a given night. This crisis has been escalating for decades. Prior to the great recession of 2008, California produced up to 200,000 new housing units per year. Despite this production, costs and the housing deficit continued to rise. After the recession, production of both single family and multi-family homes sank dramatically, recovering to only 120,000 per year statewide by 2021. The COVID pandemic and historically low capital rates over the last few years disrupted housing markets and production even further. Mounting inflationary pressures are complicating matters as they drive construction costs even higher and impact an industry that has still not fully recovered from the 2008 recession.

The California Legislative Analyst’s Office Report (2015), and California’s Housing Future (HCD 2018) study estimate the shortfall in housing production for California at 70,000 to 110,000 homes per year, resulting in a statewide deficit of approximately 2.5 million homes. California’s 2022 Statewide Housing Plan establishes the target of building 310,000 new homes each year, almost three times current production levels.

During prior years, legislative efforts have been spread across several areas of housing concern, including homelessness, tenant protections, affordable housing production, incentivizing accessory dwelling units (ADUs) and incremental approaches to increasing density in single family neighborhoods. There has also been substantial attention paid to achieving housing production goals through commercial land conversion and regeneration. Attention-grabbing, but ultimately unsuccessful, bills such as SB 50 and SB 827, focused on upzoning areas around transit. Others such as AB 3040, which focused on incentivizing the production of 4-plexes and ‘missing-middle’ housing in areas zoned for single-family residences, also failed to make it to the Governor’s desk.

During 2021, both SB 9 and SB 10 – which allow for duplexes on single family lots statewide and gives locals the ability to streamline small transit-rich housing developments – were passed and signed into law by the Governor. An early analysis by the Terner Center found that “SB 9’s primary impact will be to unlock incrementally more units on parcels that are already financially feasible.” A similar analysis by Terner of ADU legislation anticipates ADU’s may make 110,000 new units more market-feasible through-out the state over the long run. While these are solid steps forward, it is clear from California’s continued housing shortage that more needs to be done to address the state’s housing crisis.

California is also grappling with the implications of climate change. To meet state climate goals, there is increasing recognition that new homes are best located closer to job markets and where services and utilities are already in place. These locational advantages have the benefit of incrementally reducing the proportion of household budgets allocated to transportation, and support a transition to lower emission mobility options.

Various studies have found that compact and mixed use infill housing would support healthy growth with lower costs, reduced environmental impacts, and increased economic benefits. The Vision California study by Calthorpe Associates (2012) examined scenarios for California growth through 2050, finding that a more compact growth alternative, which included substantial conversion of commercial land to housing, resulted in over $7,000 (2015 dollars) per household annual savings in travel and utility costs, along with significant water, energy, and GHG reductions. Following passage of SB 375, regional plans across the state took on similar strategies, focusing planned growth in infill areas around transit and along underutilized commercial corridors. Additionally, detailed studies of the potential of commercial corridor conversion in the Bay Area and Los Angeles County have been completed by HDR/Calthorpe, EPS, and UrbanFootprint. These studies revealed that underutilized commercial corridors in just these two areas of the state could accommodate large scale infill housing without disrupting existing residential neighborhoods or displacing existing housing. This ‘Grand Boulevard’ strategy informed AB 2011’s mixed income infill housing provisions.

For the analysis of AB 2011, we applied the bill’s specific site criteria to all commercial properties in the state, evaluated the bill’s impact on zoned capacity, and applied a market-based analysis to understand where housing development would be financially feasible. We also evaluated the potential fiscal impacts of the bill and found that housing development on commercial sites generally had a positive fiscal benefit to jurisdictions. We unpack our analysis below and hope that it serves as a valuable source of information for those working to design and refine the complex policy prescription needed to tackle our state’s housing affordability crisis.

For the analysis of AB 2011, we applied the bill’s specific site criteria to all commercial properties in the state, evaluated the bill’s impact on zoned capacity, and applied a market-based analysis to understand where housing development would be financially feasible. We also evaluated the potential fiscal impacts of the bill and found that housing development on commercial sites generally had a positive fiscal benefit to jurisdictions. We unpack our analysis below and hope that it serves as a valuable source of information for those working to design and refine the complex policy prescription needed to tackle our state’s housing affordability crisis.

Our analysis estimates that, if AB 2011 were to pass, California commercial lands could increase market-feasible capacity by as many as 1.6 to 2.4 million new homes, including hundreds of thousands of income-restricted units. Importantly, the bill would likely increase the production of both townhomes and multi-family homes, and potentially increase home ownership opportunities across a wide range of incomes.

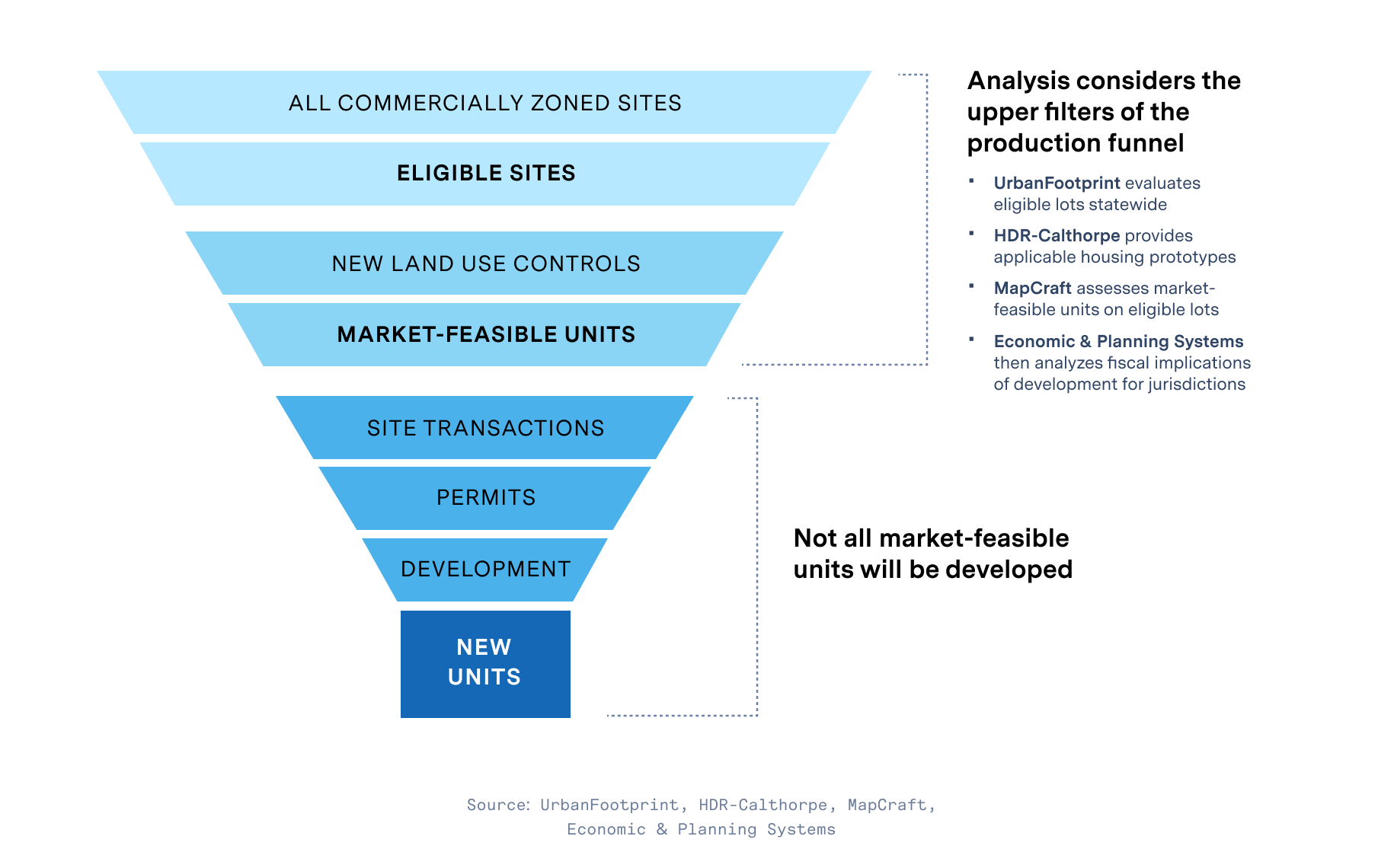

Expanding the Housing Production Funnel

There are many steps involved in getting a home built. Builders and developers must navigate a proposal through a complex process before a foundation is laid and a home is ultimately sold or rented to a resident. First, viable locations with appropriate zoning must be found, which this bill seeks to expand. The process then includes evaluating a specific site’s development allowances , determining whether the development would be profitable, purchasing the property from an existing owner who is willing to sell, obtaining necessary permits, and ultimately breaking ground for construction. A project could be derailed at any point along this path. We have called this the Housing Production Funnel, which reflects the fact that the opportunities for housing production narrow from California’s 13 million total parcels down to those that yield the state’s current production of just 120,000 homes each year.

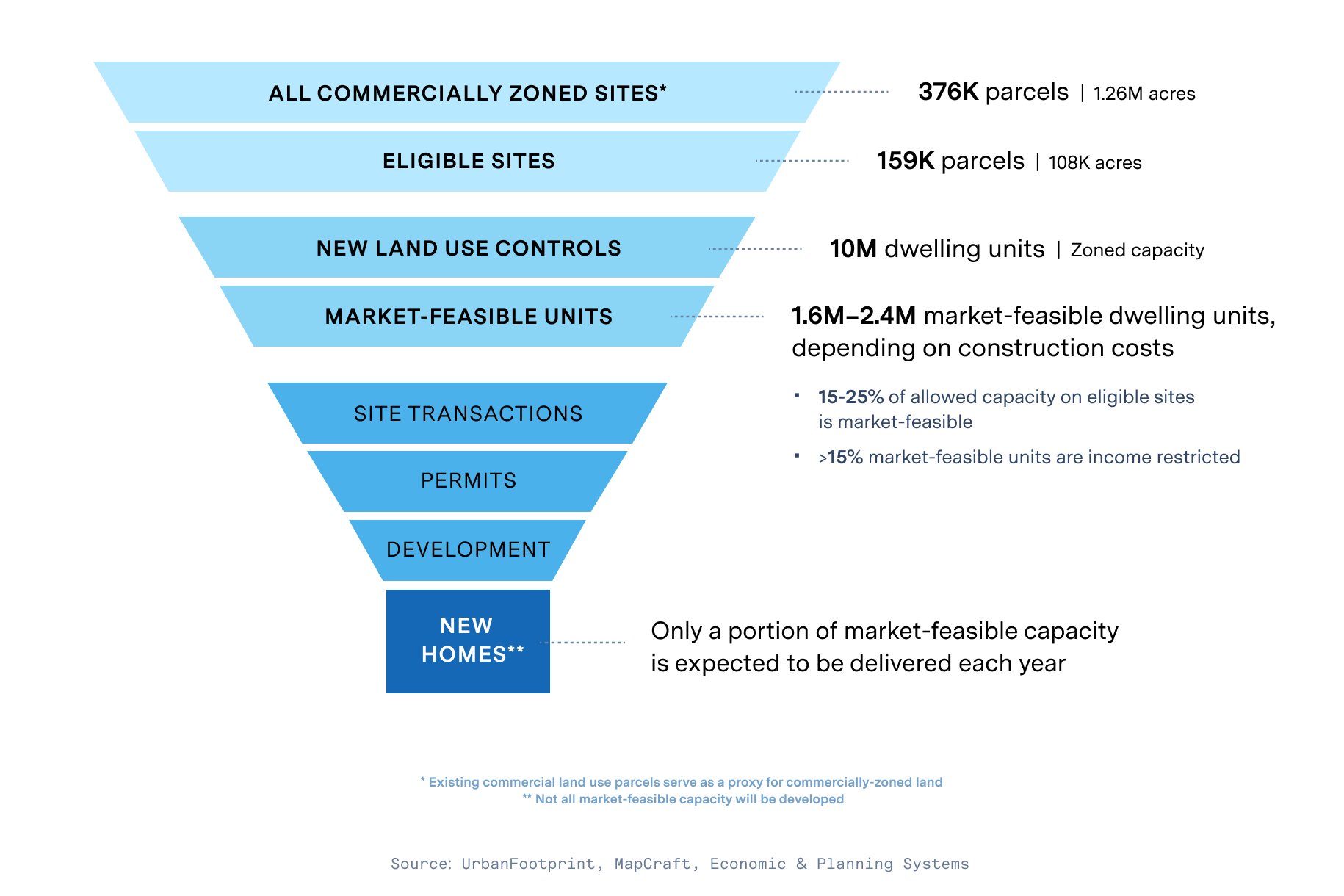

AB 2011 seeks to increase housing production by making more land eligible for residential development and easier to permit – in this case, commercially zoned land fronting an arterial roadway. For this bill, the ‘top of the funnel’ is all the land in the state currently zoned for retail, commercial, and office uses. Because of the lack of statewide zoning data, we use existing commercial land use as a proxy for zoning.

Our analysis focuses on the top two sections of the development funnel: site eligibility and market feasibility. We seek to first establish a general understanding of the number of sites on which housing could be permitted according to AB2011 standards – locations that previously allowed predominantly commercial or office uses. Second, we assess each newly eligible property to determine whether a developer could feasibly build housing based on the size and land use constraints of the site (affecting the size and type of building that could be constructed), the cost of land acquisition and construction, and the market conditions of the area. Accounting for these multiple factors on each eligible site results in an estimate of the number of market-feasible housing development opportunities that would be enabled by AB 2011.

How does AB 2011 identify commercial corridors that can be turned into new homes?

Several bills being discussed in Sacramento are focused on housing production on ‘underutilized’ commercial lands. Each of these bills specifies its own nuanced set of criteria for what constitutes an eligible commercial property, what rules are in place for what can be built, who it is built for, and even the nature of the labor force that will build the new homes.

AB 2011 concentrates on urban areas where access and amenities are already available, and allows a range of higher-intensity housing types that are already being produced by non-profit and for-profit builders and developers across California.

Specifically, AB 2011 establishes clear eligibility criteria for commercial properties, and we have used these properties as a guide to assessing developable land across California. We focused on the bill’s mixed-income housing provisions that allow development on commercial corridors, which including the following:

- Parcels that are currently zoned to allow retail, office, or parking uses.

- Parcels that abut Commercial Corridors having a right-of-way of at least 70 feet and no more than 150 feet (generally 3-8 lane roadways).

- Parcels are located inside urbanized areas as defined by the United States Census Bureau;

- There are no existing dwelling units on the parcel,

- Parcels are not adjacent to industrial sites, which is defined as any adjoining parcel where more than two-thirds of the square footage on the site is dedicated to industrial use (Includes: utilities, manufacturing, transportation storage, maintenance facilities, and warehouses. Does not include power substations, utility conveyances)

- Parcel that are less than 20 acres in size

- At least 75 percent of the site perimeter adjoins parcels that are developed with urban uses

- No part of the parcel is located within 500 feet of freeway

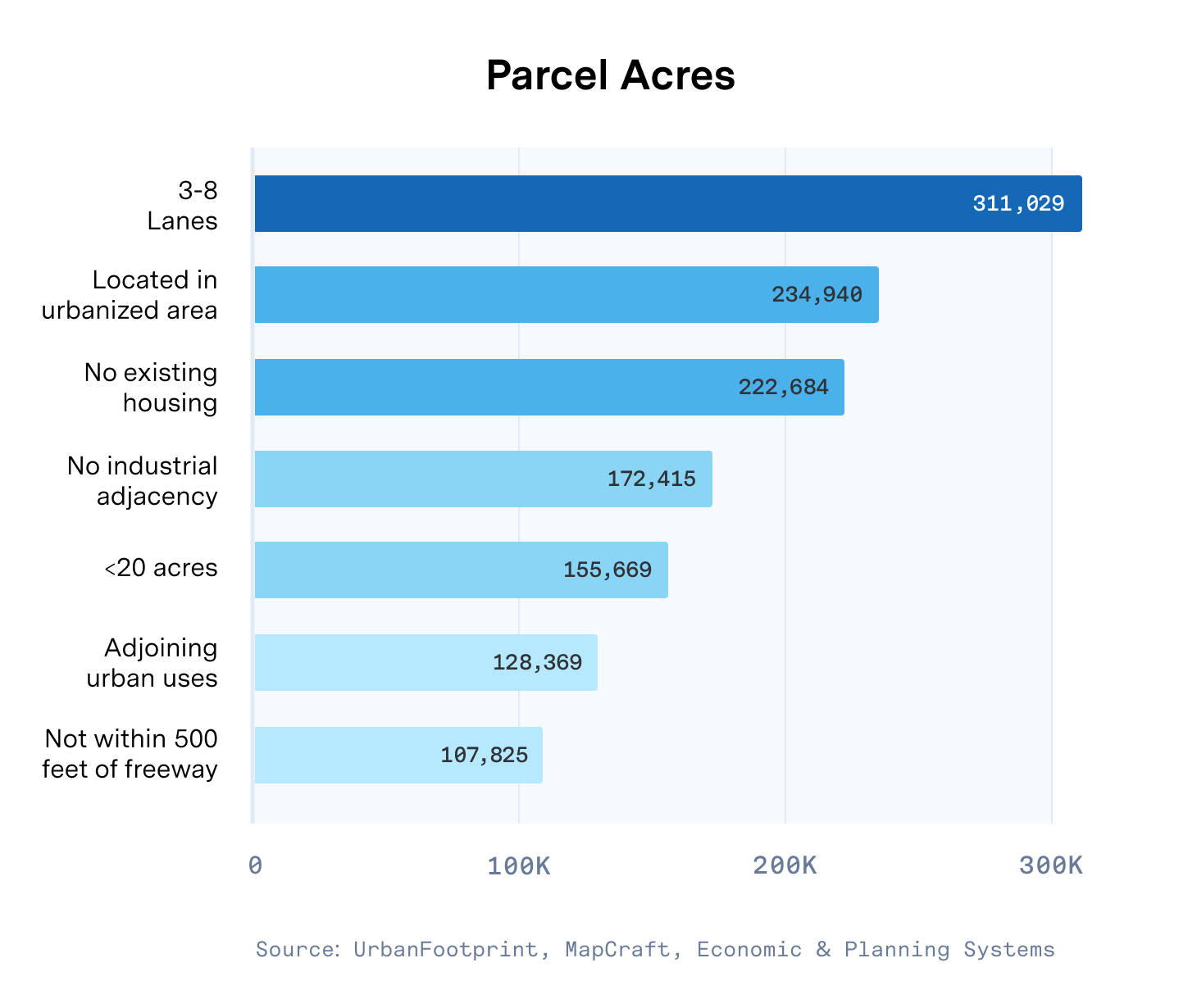

Using the UrbanFootprint Base Canvas as our source of parcel-based existing land use data, we identified 376,000 commercial properties, spanning 1,263,000 acres across the state. This includes main street properties in small towns, strip commercial corridors, large big-box sites on the edges of town, high rises and skyscrapers in downtown San Francisco and Los Angeles, and more.

With this superset of commercial parcels identified, the next step in our analysis was to apply the specific eligibility criteria laid out in AB 2011 to assess the proportion eligible for residential development. We excluded commercial parcels adjacent to industrial uses and sites greater than 20 acres (as specified in AB 2011). Of the overall 376,000 commercial parcels statewide, we found that 42% (159,000 parcels) met the AB 2011 eligibility criteria. These properties would introduce 108,000 acres of land for residential development, which is less than 10% of the acreage of all commercial parcels and roughly 0.1% of California’s total land area.

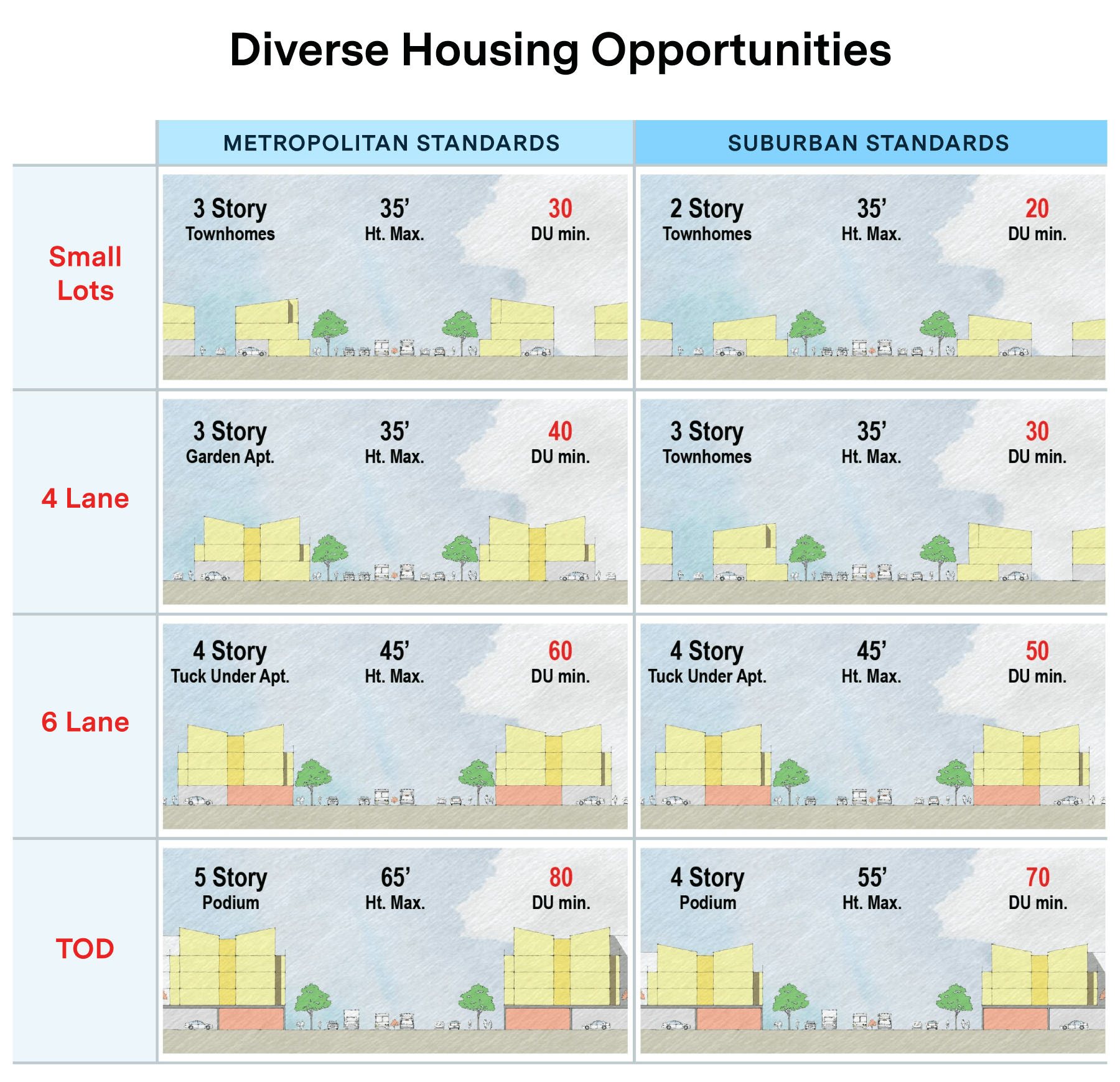

The bill then defines what is allowed on each eligible site based on a set of characteristics, including the width of the adjacent commercial corridor, the size of the parcel and the site’s proximity to transit. For each designated geography, standards are specified for minimum densities, maximum heights, and urban-design standards (see diagram below). These ‘Form Based Standards’ create a wide range of outcomes and provide different scales and types of development that can satisfy a range of housing needs. In addition the minimum densities and heights are proportional to the size of the street, the size of the parcel, and proximity to public transit. Two sets of standards are stipulated for small lots, small boulevards, large boulevards, and TODs; one for ‘Metropolitan’ areas; and one for ‘Suburban’ areas as defined by size of MSA.

Each development also has objective design standards that establish appropriate minimum rear, side and front setbacks, street frontage, and maximum heights. Reflecting these bill provisions, which are similar to an alternate zoning code for each site, HDR-Calthorpe designed efficient housing prototypes that could be developed in various corridors. Based on these designs, we calculated the minimum housing capacity of each category of eligible parcels in Metropolitan areas: 30 units per acre on small lots, 40 units per acre (UPA) could be built on sites along the narrower eligible corridors, 60 UPA on the wider eligible corridors, and 80 UPA near major transit stops. Lower minimum densities apply to Suburban areas. We determined that the bill could allow 10 million dwelling units statewide, which reflects the physical limitations of what could be built rather than what developers and investors could actually deliver given market forces.

How Many Housing Development Opportunities Does AB 2011 Produce?

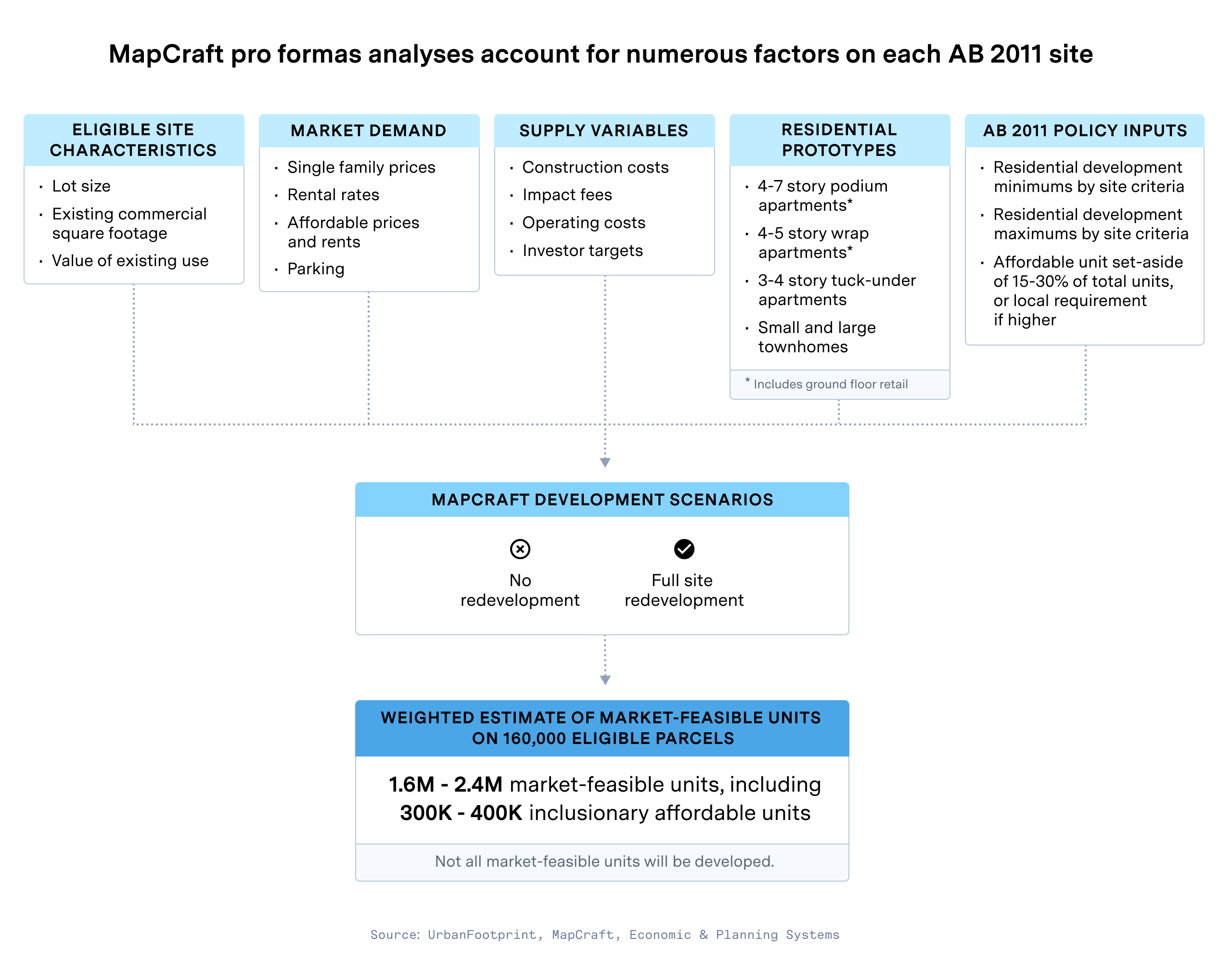

The next step in the funnel is the market feasibility assessment – that is, how much of the zoned capacity might be feasibly built given market conditions. Even if a zoning code allowed skyscrapers, market-rate developers may only build more financially viable townhomes. Real estate professionals use pro forma financial feasibility assessments to determine if a potential development investment is a worthwhile use of their resources. MapCraft used the same technique to analyze housing redevelopment potential on each of the eligible parcels to estimate the most financially viable outcome. This approach accounts for factors such as the value of the existing commercial use, construction costs, local market demand, lot size, and expected investment return. Our analysis reflected the varied developments that could occur under AB 2011’s provisions as determined by HDR-Calthorpe’s housing prototypes, including EPS’s estimates of the distinct construction costs associated with each design.

This analysis found that 15–25% (1.6M to 2.4M units) of the 10 million units of zoned capacity could be market-feasible. The low end of the estimate is based on recent construction costs. The high end of the estimate is based on a 15% reduction in today’s construction costs.

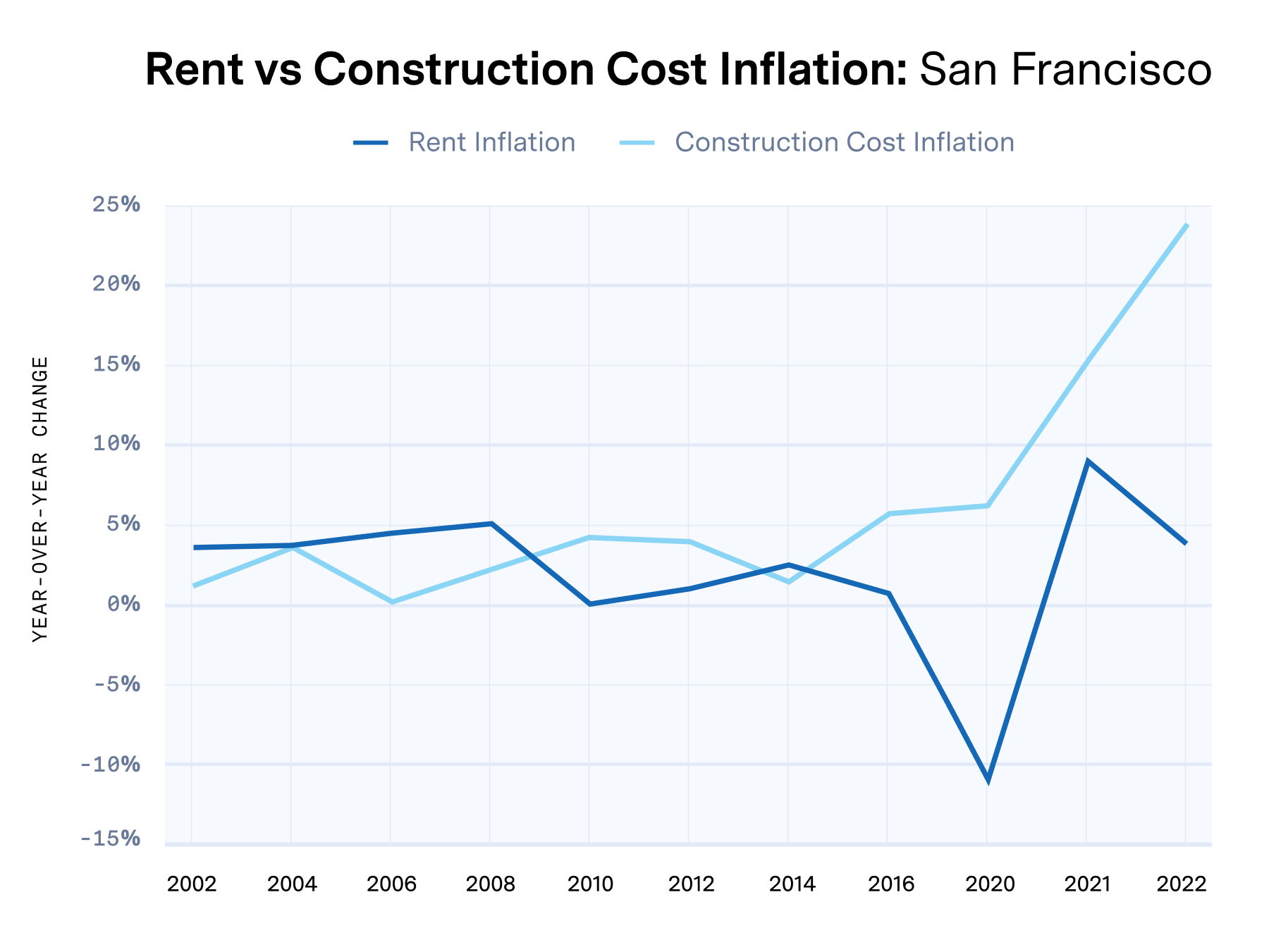

Today’s construction costs reflect extreme inflation, like the greater than 20% increase seen in San Francisco thus far in 2022 (see chart below), which is ripe for a correction. Rents and construction costs have trended together historically, but became untethered during the pandemic. Since 2020, California has seen two years of double-digit cost growth with declining or single-digit rent growth. Construction costs could be 15% lower while demand remains consistent if recent cost inflation is transitory or there is an “assembly line moment” in construction technology in response to today’s high costs.

AB 2011 Produces a Range of Housing Opportunities

AB 2011’s permitted types of housing and variety of locations leads to a range of products that support a mix of affordable, workforce, and ownership opportunities. Of the 1.6M to 2.4M market-feasible units, the analysis found that roughly 20% could be for-sale townhomes, an ownership product providing a broader set of opportunities for moderate and lower income household homeownership. Further, the bill’s requirement that a portion of the units in eligible projects be set aside as income-restricted housing results in substantial market-feasible affordable unit capacity that requires no subsidy from the state or local governments. Our analysis found that roughly 18% of the total market-feasible capacity enabled by AB 2011 would be affordable homes.

The vast majority of new market-feasible housing capacity enabled by AB 2011 would be in existing metropolitan areas with strong housing markets that support the costs of redevelopment. More than 90% of market-feasible capacity under AB 2011 is found in the jurisdictions of two Metropolitan Planning Organizations: the 9-county San Francisco Bay Area and the 6-county Southern California Association of Governments geography. Additional market-feasible capacity exists in San Diego, Sacramento, and other strong housing markets. In general, high prices and rents are required for developers to deliver mixed-income projects because high construction costs are pervasive, making development challenging across California.

While the analysis found that more market-feasible development opportunities could exist should AB 2011 become law, we cannot predict the rate at which homes will be constructed using AB 2011’s provisions. After taking into account property transaction rates, absorption, permitting, detailed site conditions, and other development factors, only a portion of the market-feasible units would be expected to be built each year. Further, the delivery of substantially more housing might require scaling up contractor capacity, the skilled labor force, material supply chains, and capital sources. But it is certain that demand for housing will remain high in the state and streamlined entitlements for development in infill areas will enhance the industry’s ability to increase housing production. If just a small proportion of the eligible sites with market-feasible capacity were to redevelop annually, then AB 2011 could amount to tens of thousands of new California homes each year, a substantial increase over recent multifamily housing production trends (see chart below).

What are the fiscal implications of commercial corridor regeneration?

Our partner in this and other studies, EPS has been working with cities on the economic feasibility of redevelopment of strip commercial sites, and have recently presented their findings in presentations on Rethinking the Fiscal Paradigm: Retail versus Housing and to CivicWell.

The economics of commercial strip development have changed for everyone, including developers, retailers, the local community and cities themselves. Since 2008, the number of new retail jobs has plateaued and is in decline. Over the last 10 years, e-commerce has grown from 4.8% (2012) of retail activity to 14.2% in 2022. Partly as a reaction to the pandemic, consumers are preferring experiential or place-based retail, rather than service based. Coupled to this transition in expectations by the consumer, the United States has a glut of retail space, having as much as 10-times as much space as other developed countries with similar GDP per capita.

Retail follows rooftops and foot-steps. Housing development increases local retail spending, as new households typically increase their expenditures, and merchants have historically benefitted from proximity to their customers. From studies conducted by our partners EPS, increasing residences helps drive increase in sales, even if actual square footage of stores declines. Additionally, vertical and horizontal mixed-use housing development can support the revitalization of struggling commercial corridors, leading to more foot-traffic and increased commercial activity overall. Where redevelopment of commercial corridors has been adopted by local jurisdictions, like Oakland’s Broadway Valdez Plan, the regeneration has produced tangible improvements for the jurisdiction.

Property taxes are the most important contributor to city revenues. Across California, notwithstanding local differentiations, property taxes contribute on average 45% general fund revenues to city general funds, approximately 2.5-times the contribution of sales tax revenues. Redevelopment of a property facilitates the resetting of the assessed value of an asset to a higher market value. Cities also gain more than just property tax when this re-assessment occurs. Importantly redevelopment may help unlock the difference between market and assessed values of properties that have been suppressed, particularly as retail has typically a lower assessed value in comparison to other land uses. Accelerating the regeneration or redevelopment of commercial corridors has been proven to increase net general fund revenues (refer to EPS presentations). Recent studies in Redwood City and Fresno confirm that higher density housing is likely to increase city revenues relative to poorly performing retail centers while successful retail is unlikely to redevelop.

The potential Tax Increment Financing (TIF) opportunities associated with commercial corridor redevelopment could support new local infrastructure and affordable housing. A 2020 report by Strategic Economics prepared for the Governor’s Office of Planning and Research described the various TIF mechanisms available in California, finding that a number of factors, including the limited revenue potential of TIF mechanisms, have limited TIF uptake across the state following the dissolution of Redevelopment in California. Our analysis finds that market-feasible housing development opportunities enabled by AB 2011 could have assessed values 20 times greater than the existing commercial properties, which may be a sufficient increment for locals to pursue TIF to fund local improvements in designated commercial corridors.

What are the environmental and household benefits of corridor regeneration?

AB 2011 has the potential to take a substantial dent out of the housing supply crisis in California, but what are the other impacts of placing more housing on commercial corridors, closer to job centers and transit networks? UrbanFootprint’s analysis of the environmental impacts of corridor regeneration along the El Camino Real arterial roadway in the San Francisco Bay Area highlights a range of the environmental benefits of the type of development incentivized by AB 2011.

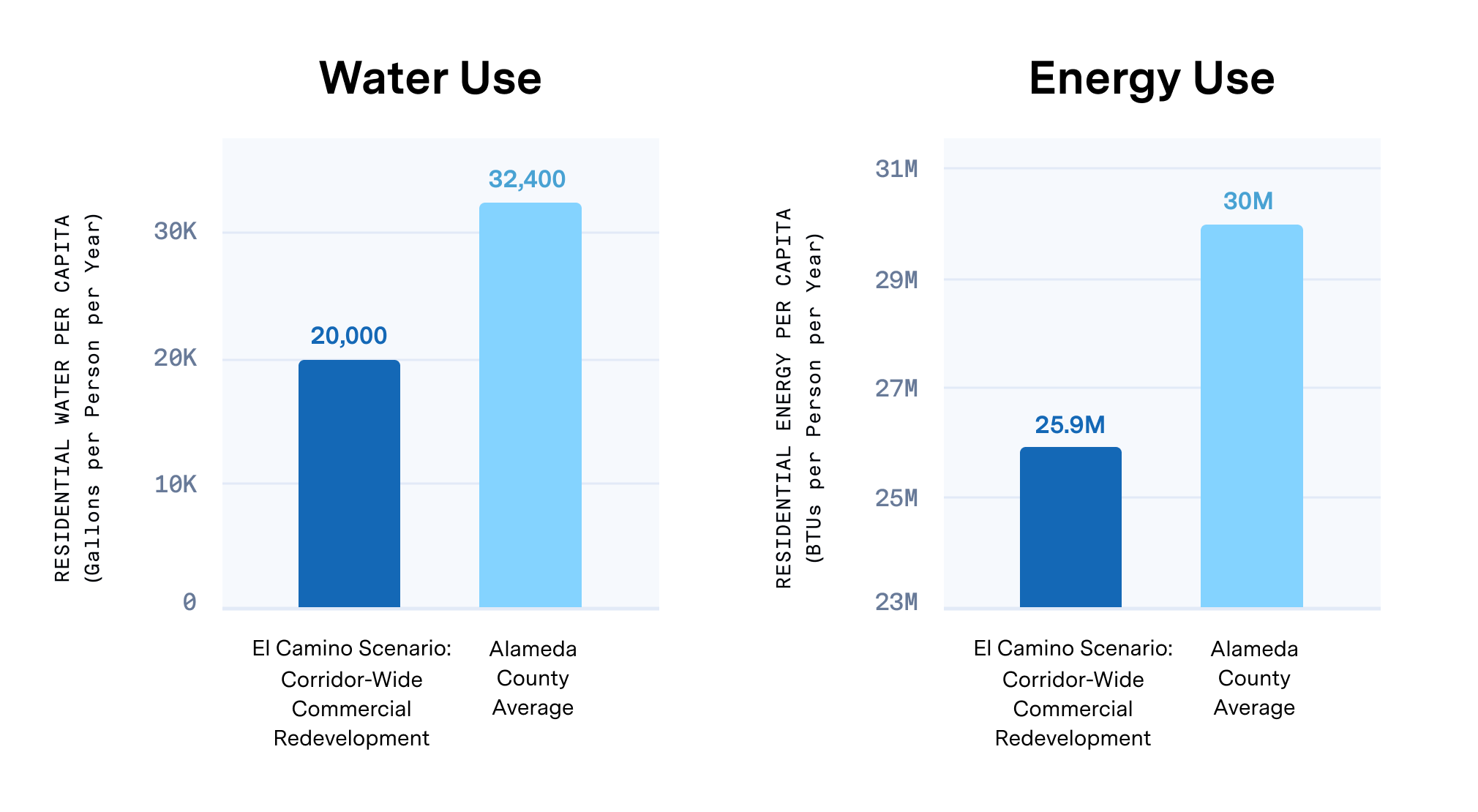

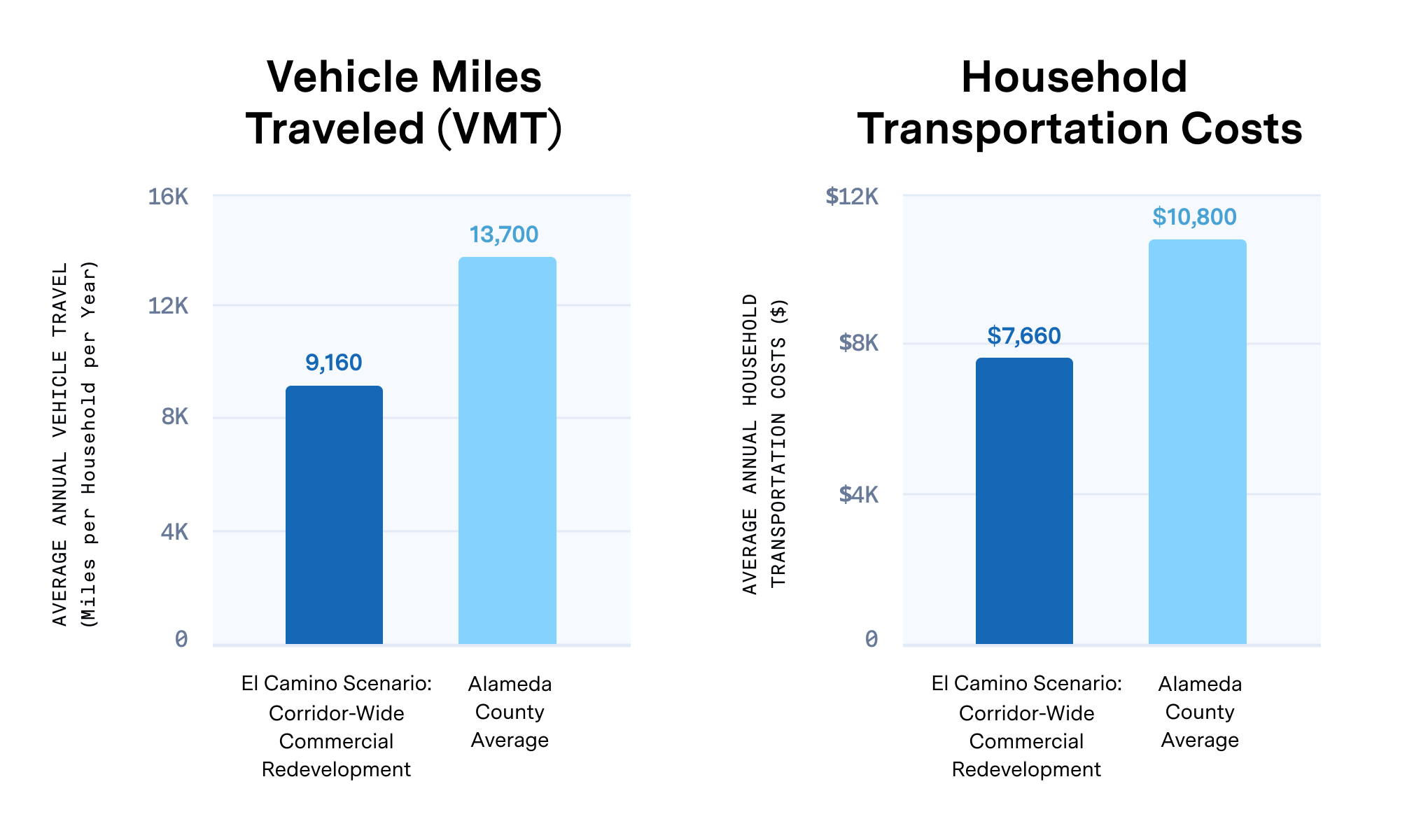

The UrbanFootprint analysis estimated that the conversion of low-density commercial parcels to moderate density residential and mixed use buildings could net as much as 250,000 additional housing units along the 43-mile El Camino corridor. When compared to average households in nearby Alameda County, new corridor households would prevent the loss of more than 16,000 acres of Bay Area open space, use dramatically less water and energy, and produce 45% fewer greenhouse gas emissions.

UrbanFootprint’s 2018 El Camino corridor study analyzed the impacts of development on commercial corridors in the San Francisco Bay Area. Compared to the average Alameda County household, new households on redeveloped strip commercial sites would consume nearly 40 percent less water per year, saving up to 5.2 billion gallons. Energy savings are also substantial, with corridor households using 13 percent less energy in their homes, the equivalent of the energy used by more than 25,000 homes in a year.

Compared to the average Alameda County household, new households in the El Camino corridor-focused scenario would drive 33% fewer miles per year and save $3,100 in annual household transportation costs.

Summary

Our analysis of AB 2011 shows that underutilized commercial corridors can play an important role in addressing California’s deepening housing crisis in an environmentally beneficial manner. Commercial corridors targeted by the bill could provide up to 2.4 million new homes, including up to 400,000 homes affordable to low and moderate income households across the state. Moreover, development stimulated by AB 2011 would most likely increase net local tax revenues.

Climate and environmental benefits are also substantial, as new households along corridors would consume far less water and energy, drive less, save money on transportation and utilities, and produce almost 50% fewer greenhouse gas emissions than the average California household. With AB 2011, policy makers are making substantial moves to address the housing and climate crises, further ensuring California remains on the leading edge of housing and environmental policy.